Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming

- Publication: The Independent on Sunday

- Date: 2003-11-16

- Author: Matthew Sweet

- Page: 6

- Language: English

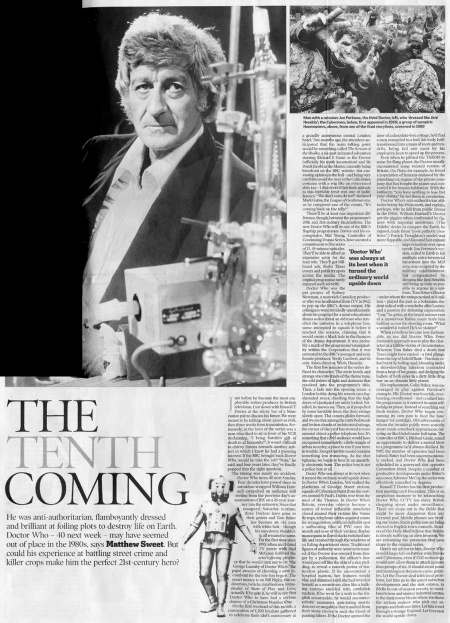

He was anti-authoritarian, flamboyantly dressed and brilliant at foiling plots to destroy life on Earth. Doctor Who - 40 next week - may have seemed out of place in the 1980s, says Matthew Sweet. But could his experience at battling street crime and killer crops make him the perfect 21st-century hero?

Just before he became the most employable writer-producer in British television, I sat down with Russell T Davies at the sticky bar of a Mancunian pub to discuss his future. We were meant to be talking about Queer as Folk, then three weeks from transmission. Fortunately, as the hero of the series was a man who liked to sit in front of his VCR declaiming, "I bring Sutekh's gift of death to all humanity!", it wasn't difficult to chivvy Davies towards another subject in which I knew he had a pressing interest. If the BBC brought back Doctor Who, would he take the job? "Sure," he said, and four years later, they've finally popped him the right question.

The timing was surely no accident. Doctor Who turns 40 next Sunday. Four decades have passed since an astrakhan-wrapped William Hartnell catapulted an audience still reeling from the previous day's assassination of JFK on a 26-year journey into the unknown. Since that inaugural Saturday teatime, three Doctors have gone to their graves and Tom Baker has become an old man with white hair - though his anecdotes, thankfully, all remain the same. For the first time since 1995, when an ill-fated TV movie with Paul McGann fulfilled the actor's gloomy prophecy that he would turn out to be "the George Lazenby of Doctor Whos," the papal process of choosing a new incumbent for the role has begun. The smart money is on Bill Nighy, the cadaverous, twitchy, tumbledown scene-stealer of State of Play and Love, Actually. If he gets it, he will be the first Doctor Who to have had a serious chance of a Christmas Number One.

On the first weekend of this month, a convocation of 1,200 loyalists gathered to celebrate their idol's anniversary at a grandly anonymous central London hotel. Two months ago, the attendees anticipated that the main talking point would be something called The Scream of the Shalka, a six-part animated adventure starring Richard E Grant as the Doctor (officially his ninth incarnation) and Sir Derek Jacobi as the Master, currently being broadcast on the BBC website. But canvassing opinion in the hall - and being very careful to avoid the man in the Colin Baker costume with a wig like an eviscerated shih-tzu - I discovered that their attitude to this birthday treat was one of indifference. "We don't care, do we?" declared Mark Gatiss, the League of Gentlemen star, as he compered one of the events. "It's coming back on the telly!"

There'll be at least one important difference, though, between the programme's 20th and 21st-century incarnations. The new Doctor Who will be one of the BBC's flagship programmes. Davies and his co-conspirator, Mal Young, Controller of Continuing Drama Series, have secured a commitment to five series of 13, 45-minute episodes. They'll be able to afford an expensive actor for the lead role. They'll get billboard ads, Radio Times covers and publicity spots across the media. The original programme rarely enjoyed such security.

Doctor Who was the pet project of Sydney Newman, a maverick Canadian producer who was headhunted from ITV in 1962, to pep up the BBC's drama output. His colleagues were decidedly unenthusiastic about his proposal for a semi-educational drama series about an old man who travelled the universe in a telephone box; some attempted to squash it before it reached the screens, claiming that it would create a black hole in the finances of the drama department. It was probably a mark of the programme's marginality within the Corporation that it was entrusted to the BBC's youngest and only female producer, Verity Lambert, and its only Asian director, Waris Hussein.

The first few minutes of the series defined its character. The eerie howls and strange staccato thuds of the theme tune, the odd pulses of light and darkness that resolved into the programme's title. Then, a fade into the opening scene: a London bobby doing his rounds on a fog-shrouded street, checking that the high doors of a junkyard are safely locked. Satisfied, he moves on. Then, as if propelled by some invisible force, the door swings slowly open. The camera glides forward, and we see that among the rusty bedsteads and broken chunks of architectural salvage, the owner of the yard has stowed a more unusual object: a police telephone box. It's something that a 1963 audience would have recognised immediately: a little temple of urban security; a place to run if you were in trouble. Except that this model contains something less reassuring. As the shot tightens, we begin to hear it: an unearthly electronic hum. The police box is not a police box at all.

Doctor Who was always at its best when it turned the ordinary world upside down. In Doctor Who's London, Yeti stalked the platforms of Goodge Street station, squads of Cybermen burst from the sewers around St Paul's, Daleks rose from the mud of the Thames. In Doctor Who's Britain, everyday objects became a source of terror: inflatable armchairs closed around their victims like Venus fly traps, telephone cables acquired a taste for strangulation, artificial daffodils spat a suffocating film of PVC over the mouth and nose of their victims; display mannequins in flared slacks twitched into life and crashed through the windows of an Ealing department store. Traditional figures of authority were never to be trusted: if the Doctor was rescued from danger by a policeman, the officer's face would peel off like the skin of a rice pudding, to reveal a smooth patina of featureless plastic. If he encountered a hospital matron, her features would blur and shimmer until she had revealed herself as a monstrous alien like a hulking embryo studded with cuttlefish suckers. If he went for a walk in the English countryside, he would encounter robotic mummies, gun-toting morris dancers or megaliths that trundled from their stone circles to suck the blood of passing hikers. If the Doctor opened the door of a chocolate-box cottage, he'd find a man manacled to a bed, his body half-transformed into a mass of roots and tendrils, being fed raw meat by his employers, keen to speed up the process.

Even when he piloted the TARDIS to some far-flung planet, the Doctor usually encountered some twisted version of Britain. On Pluto, for example, he found a population of humans enslaved by the punishing tax regime of the private company that has bought the planet and converted it for human habitation. With the battlecry, "you have nothing to lose but your claims," he led them to revolution.

Doctor Who's anti-authoritarian attitudes betray his 1960s roots, and explain, perhaps, why he fell from public favour in the 1980s. William Hartnell's Doctor got the giggles when confronted by figures with imperial ambitions. (The Daleks' desire to conquer the Earth, he argued, made them "poor pathetic creatures".) Patrick Troughton's model was more flappable, and favoured last-minute improvisation over open revolt. Jon Pertwee's version, exiled to Earth to foil multiple extra-terrestrial incursions into the M25 area, was co-opted by the military establishment, but compensated by dressing like Jimi Hendrix and being as rude as possible to anyone in a uniform. Tom Baker's Doctor - under whom the ratings peaked at 16 million - played the part as a bohemian student radical with a wardrobe after Lautrec and a passion for defeating expectation: "I say," he grins, as the brutal manservant of a mysterious Italian count hurls him halfway across the drawing room. "What a wonderful butler! He's so violent!"

When rebellion became less fashionable, so too did Doctor Who. Peter Davison's approach was to play the character as a fallible victim of circumstance. Whereas Tom Baker died a death that Tosca might have envied - a fatal plunge from the top of Jodrell Bank - Davison exited burnt by boiling mud, labouring under a skin-shredding infection contracted from a heap of bat guano, and dodging the bullets of both sides in a dirty little drug war on an obscure little planet.

His replacement, Colin Baker, was encouraged to play against Davison's example. His Doctor was boorish, overbearing, overdressed - and crashed into the programme as it entered its most self-indulgent phase. Instead of searching out fresh terrors, Doctor Who began consuming its own past to feed the fans' hunger for nostalgia. Old adversaries of whom the broader public were scarcely aware made comeback appearances, tottering on liked faded music hall turns. The Controller of BBC 1, Michael Grade, seized an opportunity to deliver a mortal blow to a programme he'd always disliked. By 1987, the number of episodes had been halved, Baker had been unceremoniously sacked, and Doctor Who had been scheduled in a graveyard slot opposite Coronation Street. Despite a number of productive developments under Baker's successor, Sylvester McCoy, the series was effectively cancelled by degrees.

Russell T Davies has his first production meeting on 8 December. This is an auspicious moment to be relaunching Doctor Who. CCTV has every British shopping street under surveillance. There are crops out in the fields that might be more dangerous than any Krynoid pod. Mobile phones are broiling our brains. Racist politicians are being elected to English town councils. Readers of the Daily Mail believe that Britain is already suffering an alien invasion. We are relearning the paranoias that gave shape to the original series.

Here's my advice to him. Doctor Who should forgo full-on battles with Daleks and Cybermen, even if CGI technology would now allow them to attack in more than groups of six. It should avoid passé and meaningless threats to entire galaxies. Let the Doctor deal with local problems. Let him go to the gated suburban developments and the sink estates, to B&Bs in out-of-season resorts, to moribund towns and sinister industrial estates, to the dank tower blocks where we shove the asylum seekers who pick our asparagus and froth our lattes. Let him travel through a strange England. Let him turn the world upside down.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Sweet, Matthew (2003-11-16). Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming. The Independent on Sunday p. 6.

- MLA 7th ed.: Sweet, Matthew. "Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming." The Independent on Sunday [add city] 2003-11-16, 6. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Sweet, Matthew. "Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming." The Independent on Sunday, edition, sec., 2003-11-16

- Turabian: Sweet, Matthew. "Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming." The Independent on Sunday, 2003-11-16, section, 6 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Doctor_Who:_The_Tenth_Coming | work=The Independent on Sunday | pages=6 | date=2003-11-16 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=26 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Doctor Who: The Tenth Coming | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Doctor_Who:_The_Tenth_Coming | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=26 December 2025}}</ref>