Difference between revisions of "The Children are Watching"

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{article | + | {{Blishen}}{{article |

| publication = Contrast | | publication = Contrast | ||

| file = http://cuttingsarchive.org/images/6/60/1964-10-01_Contrast.pdf | | file = http://cuttingsarchive.org/images/6/60/1964-10-01_Contrast.pdf | ||

Latest revision as of 00:35, 12 February 2018

- Publication: Contrast

- Date: autumn 1964

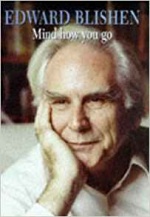

- Author: Edward Blishen

- Page: 242

- Language: English

Over the first few months of this year I spent a good many hours between five and six o'clock of an evening in a world unknown, I imagine, to many adults and only fleetingly known to others : the world of children's television. I was drawn partly by curiosity : and an element in that was my observation that children's TV seemed to have made little mark on my own sons. I could remember the effect on myself and on my con temporaries of Children's Hour on sound. In its heyday, of course, before the war, Children's Hour spoke to an audience less sophisticated than today's. Miracles were thinner on the ground. Radio was still something of a lone astonishment. Childhood itself was a less ambiguous condition that it now is : and children shared far less than they do today in the culture of their elders. Nevertheless, the impact of Children's Hour was great I am constantly running into people of my own age to whom Mr. Growser, of Toytown, is still the epitome of officious bad-temper : who recall with gratitude the quiet deep voice of Stephen King-Hall explaining current events : who still remember the talks and discussions they heard, the wide variety of drama, and the little group of regular broadcasters who gave the programmes their editorial consistency, their centre and coherence. (They'd begun, one remembers, as uncles and aunts, but shed this pretence of relationship for a cooler but still firm one as the tide of sophistication rolled on).

It is true that, in the course of time, Children's Hour began to lose listeners because it was always, essentially, middle-class. It came to have little to say to a rather large group of the nation's children. (Especially to those who have never comfortably confessed to being 'children'). It failed to touch those who weren't already given to reading good books or disposed to listen quietly to talks and discussions. It always worked within certain limits of accent : and as an ex-secondary modern teacher in London I know how simply blank the conventional middle-class accent heard on the BBC can leave a good many children. It doesn't seem to be talking to them. Moreover, Children's Hour failed to do what good schools are now attempting : to acknowledge that certain notions of entertainment exist widely among children (to be summed up, whether it's a matter of reading or music or whatever, as 'pop'), and that an advance towards higher standards can be achieved only if first these widespread notions are looked at. You don't work towards a more discriminating view of music by pretending that 'pop' music doesn't exist. You begin there : you look at 'pop' music critically : you begin to suggest that some of it may be better and some worse: you lay it side by side with other things : you do all this goodhumouredly, without priggishness, for the fun of it; and your audience may cease to run away, may listen, may come to see the pleasure of discrimination and the joy of rejecting what's bad, false or meretricious. This Children's Hour didn't do, in relation to music or anything else : and towards the end, and particularly when television became a rival, it paid the price in the form of a calamitously dwindling audience.

Yet it had made its impact : it was a good service, with standards, a high sense of responsibility, an understanding of children - even if there were limits to that understanding : and one question in my mind, as I began my viewing, was why children's television seems to have had an effect so much slighter. I was also anxious to see what use television had made of its greater freedom. Some of the inhibitions that lay on sound seem never to have affected the more recent service. The old limits of accent - and the other limits that accompany that one - appear not to haunt it. Surely, I felt, here if anywhere must be a service that sought to raise standards, good-humouredly, that could afford to be experimental, and that would in general be making bold use of its really remarkable opportunity.

I was, I must say, quite drearily disappointed. My first general conclusion is that children's TV is • (on both channels) a miscellany without a heart. The programmes simply happen. There is very little sense of editorial continuity. It is true that the programmes have special announcers, that many of these are charming and that they give the service some sort of identity. But it is the identity given by a compere, not that, far deeper, given to Children's Hour by its regular and familiar presiding broadcasters. I frankly don't understand why a feature of television that must necessarily be of the nature of a magazine should be denied its guiding characters. With children, especially, I should have thought they were essential: as essential to them as Cliff Michelmore is to the adults who watch TONIGHT, or Richard Dimbleby to those who watch PANORAMA.

A sense of considerable vagueness of direction, then, seems to me to haunt the programmes. One simply doesn't feel there is behind them the kind of presence that a children's book editor contributes to the books published by her firm, or the shaping and binding influence exerted on a good children's magazine by its editorial staff. It may be because of this that so many of the programmes seem to be unexacting junior forms of light entertainment. In a typical week, commercial television devoted two-thirds of the total time given to children to films that were mostly of a low-quality, slot-filling kind, a 'pop' club programme, a quiz and a cartoon. For banality and lack of all flavour, some of the films have to be seen to be believed : my own children at one time had entertainment from them, of a kind not intended, by way of hilarious anticipation of the next obvious action or remark. (If you want to get out of this town alive, kid...') They were on the target nine times out of ten. It's true that ringing the changes on great clichés - Once upon a time' is one - is part of children's entertainment, at some stage : but this is cliché faded like a hundredth carbon-copy. One begins to ache, after a while, at the very idea of actors, producers, cameramen, being driven through this ritual of weary commonplace. The 'pop' club programme, to my mind, might as well be identified as plain advertisement: it sells to children a product as clearly commercial as a detergent, performed by groups or individuals who are loudly acclaimed as 'artists', but might as well have been shaken out of cartons. In saying this, I am not moved by animus against popular music. But I do question the health of a service for children and young people that merely adds to the number of those programmes, already multitudinous, that are plain shop-windows for the manufacturers of 'pop'. If there is one part of television that ought to resist a link with 'show biz', it is children's television. As for the quizzes -- nearly everyone loves a quiz: but why, one must ask, so many of them? And why is the presentation, especially on the commercial channel, so gimmicky, so fraught with that factitious tension that is the mark of the adult television quiz (because each quiz programme is so anxious to distinguish itself, in some desperate difference, from all others of the kind). The natural tension of the quiz is surely enough. And it really is, at all levels of television, horribly overdone. The cartoons vary enormously in quality - and here again it is true that nearly everyone loves a cartoon, or at least sets out to watch one with the intention of loving it if possible: and that we can have too many of them. (I have, incidentally, lost friends since publicly declaring elsewhere my affection for BOSS CAT, shown on BBC children's television : but this sort of thing is bound to make people glower at one another while they argue about what is vulgar).

The BBC's typical week is better than this : some of the very best films to be seen on children's television and a few are extraordinarily good - are to be found in that channel. Nevertheless, in a typical week the BBC gave more than half its time to the same unexacting type of programme. The worst of BBC fare, to my mind, is the programme of which the unlamented CRACKERJACK is the archetype. This was a sort of very long, horribly jocular children's party. Quizzes, competitions, pop songs, and comic sketches of a kind that passed far beyond embarrassment were the ingredients. There were an awful lot of avuncular adults around. (The presiding spirit of CRACKERJACK, of course, Eammon Andrews, formed a link with similar cosy programmes on adult television). Very seriously, I question whether a formula such as this is good enough for children. It's not that I'm against weak jokes : children love them, and agreeable adults have a soft spot for their occasional emergence. It's not, either, that I'm against parties. But I don't see how either weak jokes or parties can be defended as staple elements in a service of children's television. They usurp space and time that might be filled with funnier - gayer, better and more entertaining - things. I don't think, anyway, that deliberate displays of bonhomie are ever good for children. The aunt-ness and uncle-ness of the leading characters in primitive Children's Hour rested on a tradition of kindly concern : this other chumminess is that of the clubman, over-hearty and making your back shrink from the jocular slap that seems always imminent.

Of course, there are good - there are even marvellous - things on children's television. I hardly have to say that they include the BBC's great serials. The unbroken success of these serials is almost unnerving. How easy to destroy the curious victorian magic of THE SECRET GARDEN - how beautifully it was caught and kept! How rapidly, in weekly instalments of twenty minutes, the tension of LORNA DOONE might have been lost—how triumphantly it was preserved!

Has there been a single better individual performance anywhere in television than Patrick Troughton's Quilp in THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOP? With what boldness the producer was able to fade from the original illustrations to MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT into the scenes created by his designers - because here was the world of those original creatures brought to life with utter fidelity! It can't have been with small budgets that these highly imaginative and honourable re-creations were produced : yet they do lead one to ask why, as summits, they are so lonely. Why is there so little other direct drama in children's television? Where are the foothills of regular inexpensive dramatisation? DR. WHO has been great ridiculous fun : but had it to go on so long? And couldn't some of the money devoted to it have been spent on a more regular - and more modest - diet of drama? One asks this, if for no other reason, because its plays, its serial dramas, were always the heart of Children's Hour : and for the good reason that these are among the things children need and love. Films simply aren't the same thing.

Watching all this, I tried to work out a general pattern. I think the smaller children do rather well. SMALL TIME on commercial television is lovingly and expertly done. I fancy this may be because it's more obvious that you must make an effort to understand the needs of the very young - you must call upon those who really know the field. Again, with the very young you move within a limited budget without feeling you are doing wrong : you can use puppets and drawings and simple props. (I wish it wasn't felt, as it seems to be, that similar economy of means is out of place when it is older children who are being addressed). For the rest, the pattern seems very haphazard. The young person interested in animals does well, here as elsewhere in television - I. think he might do too well, and grow at last indifferent even to the spectacle of badgers scratching one another's backs. Sport is well catered for : and the BBC, especially, keeps an eye on the young person as someone with hobbies and pets and a general curiosity about the ways things are done or made. In this field, there is nothing better on either channel than the BBC's BLUE PETER, which is a programme that for once seems to be guided and run by sensibly matter-of-fact adults, who never talk down or slap backs, and who fix their attention on the substance of what they are doing, letting manner (in the broadest sense here) look after itself.

But beyond these flashes of virtue, one must say that the programmes are highly unambitious. I came to the conclusion (knowing that television is far easier to criticise than to create) that there were two major reasons for this. They are probably linked reasons. The first is that the over-riding aim appears to be to keep abreast with what is known to be the lowest common denominator of young needs : to follow taste, rather than to attempt to create it : to echo activity, rather than to set it going. There is so little that is original or experimental. Absolutely no original, purely televisual, form of children's entertainment has emerged. Among the adults who appear on it, one can't think of a radically fresh character. There isn't even a single strand in the programmes of which one can say: 'Ah, behind that is someone who sees that television might extend the world of children and young people - might set new things going'. Of course, a restlessly radical and experimental service would be intolerable. But it is the conservative side of children's natures that appears on the whole to be catered for : the other, progressive, side is left out of court. Well, anyone knows who works among children how easy it would be to become infected by childish conservatism. This happens at times to whole schools - a condition that leads in the end to bad behaviour, rebellion, because the experimental side of a child's nature can't bear to be forever starved. (It's obviously possible to see the disturbances at seaside resorts in terms of our failure to provide young people with opportunities for constructive experiment). I would think that children themselves should have far more to do in, and with, television than they are allowed. What a feeling of thwarted energy one gets when listening to the BBC's JUNIOR POINTS OF VIEW. Why shouldn't groups of children occasionally run a day's - or a week's - programmes'? Why doesn't children's television look more often, more informally, at what, here and there, children themselves are doing? There seems little to be lost by experiment. As it is, the service seems to lag a long way behind the best things being done in good schools and clubs. And this brings me to the second reason that I suspect to lie behind the unambitiousness of the programmes. There doesn't appear to be at work the kind of mind that understands the children's world and has a proper eagerness to extend and stimulate it. I can't see why otherwise we should see, for example, an artist teaching children to draw according to formula : a thousand art teachers, if this sort of programme has any effect, must be trying to drag their children back into the twentieth century.

A lowness of aim, then, is the chief criticism. While I was doing my stint of viewing, and since, I have spoken about children's television to a good many young people. I find that they, too, have a restless feeling that it could be a bigger and bolder and more exciting element in their lives. Perhaps the biggest indirect comment they have made is in providing for THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOP a quite enormous audience - nearly four million. This does suggest that they can take a much more ambitious diet than they are now provided with. But personally, I've never had any doubt of this. After fifteen years of teaching I came to the firm conclusion (and it wasn't cosy teaching) that we under-estimate the spiritual stamina of young people everywhere. We feed them, in too many fields, according to mild old formulae. We give them too little to bite on. We lay too little on their shoulders. We involve them too little. A service of children's television ought surely to be in the forefront of those who are trying to correct this situation. After all, makers of television don't suffer from the habits that inhibit so many teachers. Television doesn't begin with an incubus of respectability. It is quite dramatically free. I would suggest that any one who suspects I have put this all far too strongly should watch children's television for a week - two or three evenings would do - and then should ask himself. Is this a service with a proper sense of the responsibility that arises from its quite new and immensely exciting opportunity?

Caption: DR. WHO (BBC). Carole Ann Ford and William Hartnell.

Caption: THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOP (BBC). Patrick Troughton as Quilp

Caption: SMALL TIME (Rediffusion). Muriel Young, Pussy Cat Willum, Wally Whyton

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Blishen, Edward (autumn 1964). The Children are Watching. Contrast p. 242.

- MLA 7th ed.: Blishen, Edward. "The Children are Watching." Contrast [add city] autumn 1964, 242. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Blishen, Edward. "The Children are Watching." Contrast, edition, sec., autumn 1964

- Turabian: Blishen, Edward. "The Children are Watching." Contrast, autumn 1964, section, 242 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=The Children are Watching | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Children_are_Watching | work=Contrast | pages=242 | date=autumn 1964 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=The Children are Watching | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Children_are_Watching | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 December 2025}}</ref>