Difference between revisions of "You'll believe a Dalek can fly"

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{article | {{article | ||

| − | | publication = The Sunday Telegraph | + | | publication = The Sunday Telegraph (England) |

| file = 2005-03-20 Sunday Telegraph.jpg | | file = 2005-03-20 Sunday Telegraph.jpg | ||

| px = 500 | | px = 500 | ||

Latest revision as of 10:27, 31 December 2024

- Publication: The Sunday Telegraph (England)

- Date: 2005-03-20

- Author: Russell T. Davies

- Page: Review, p. 7

- Language: English

'Doctor Who' returns this week. Prepare to be scared, says Russell T. Davies, its new scriptwriter and lifelong fan remember shop-window dummies coming to life. I remember maggots. I remeber devils coming out of the sea, an evil plant bigger than a house and a Frankenstein's monster with a goldfish bowl for a head. And if you're somewhere over 35, you might remember the same things. That's Doctor Who, the show that burned its way into children's heads and stayed there for ever, as beautiful and vivid as a folk tale.

Now the good and constant Doctor is coming back, and I'm one of those in charge of it. This week, I'm trapped in the tornado of the BBC publicity machine as the launch, on Easter Saturday, approaches. I'll do anything to sell this lovely show.

If hype is the name of the game, then I'll hype with the best of them. So I find myself in bizarre situations: sharing crisps with Mariella Frostrup on Radio 2; sitting in the Breakfast News green room with Fearne Cotton, wondering how old I must look to her, walking down Old Compton Street and being stopped on three separate occasions by men - bless the faithful gay men! - wishing us luck. And I wonder how it happened; how that old childhood fantasy came back to life.

When I was young, Doctor Who had yet to be associated with that terrible, limiting word "cult". In the 1960s and 1970s, it seemed as though everyone watched it. I remember one day in junior school, my little gang - John Dyke. Stephen Banfield ... where are they now? - huddling together over the desks on a Monday morning and wondering how the Doctor would escape from his latest encounter with the Daleks.

"Their guns don't work." We turn round, John and Stephen and I; the supply teacher is standing by the blackboard, chalk in hand. And he explains. "The city's draining all the power, so the Dalek guns don't work." And he was right! He'd guessed the resolution to the cliffhanger, and Mr Whoever-he-was became the only supply teacher in history to earn any respect. I hope he's a headmaster now.

In hindsight, I wonder if I was hooked by the very thing that later condemned the programme - wonderful cheapness combined with wonderful ambition. An invasion of Earth, with three soldiers? Done. Green bubble-wrap as a monster? Check. The aforementioned goldfish bowl as the repository of the galaxy's greatest evil genius? Absolutely!

I think the gaps in production made the viewing experience interactive long before digital television was invented. The gaps in the finished product allowed

mind inside, whereas Star so glossy and perfect and shining, seemed closed: it made you watch, not participate. With Doctor Who, we watched what was, and imagined what could be.

Consider that formative memory, the shop-window dummies coming to life and invading the high street. In memory, there's the most wonderful moment as the dummies, trapped in store-front displays, walk forward, raise their arms, chop downwards, and shatter the shop window into a thousand pieces. But watch the actual episode - Spearhead from Space (1970), still a wonderful piece of telly to this day - and, yes. the dummies spring to life; yes, they walk forward; yes, they raise their arms and chop down... But no glass smashes. It must have been too expensive! Instead, we cut to a shocked policeman, turning round as he hears the glass smash. A brilliant solution, but my false memory is every bit as valid as the transmitted version.

So as I watched, I imagined my own versions, my own stories, my own epic quests. I'd love to tell you I was 12, but this went on for years. I was a student at Oxford University in the early 1980s, still wondering if the Claws of Axos (1971) deserved a sequel. My head would boil with stories! In fact, I think Doctor Who made me a writer. I believe it instilled in me an appreciation of plotting, pacing, a thrill followed by relief, the need for a joke in a moment of tension. Whether I'm writing soap opera or space opera, I've remembered those lessons.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, the years passed and Doctor Who's reputation declined, and sometimes it felt as though I was the only one still watching. Those lovely gaps in the production became the only thing that we remembered.

I wonder, sometimes, if we get embarrassed by our childhood passions and rubbish them in order to prove that we're adult. I certainly went into denial. I remember a potential boyfriend in Manchester spotting a Doctor Who book in my flat and claiming that he'd been an extra in The Caves of Androzani (1984). I pretended I didn't know what he was on about. I think I said I was looking after the book for someone else, or something. There are many forms of closet.

But time kept on passing, and I kept on loving this show. Slowly I discovered fandom, that most reviled and misunderstood minority status. Doctor Who fans are brilliant. When the series fell off air in 1989, they kept inventing - producing novels, comic strips, audio adventures and webcasts.

Of course, fandom discussions are always dominated by the unfortunate few, the fevered letter-writers whose love has turned to necrophilia. But fandom is a broad church. Although the loud lunatics always get the attention, the normal, happy fan is the wittiest, most television-literate person you could hope to meet.

For all that. fandom is not enough to resurrect a television series on its own. But I knew that the series had once been loved by all, not just a few. I reckoned that, one day, a generation would pass, and people would remember that love and seek to create it anew. I supposed that this might be 20 years away - that the 2020s might see the Doctor reborn. But I didn't notice myself getting older - I still think I'm 21 - and I failed to notice that a generation had already passed. Until the telephone call came from the BBC. Would I like to bring back Doctor Who? Well, what do you think I said?

The first decision, one that required no debate at all, was to respect this new generation and make the new show for them. It's still the same show, the same Doctor - no Superman-Smathrille-style rebooting needed, since the Doctor has already changed his face many times - but we can't rely on assumed goodwill from anyone under 25. This new adventure starts from scratch.

The basic concepts are so wonderful, we almost forget quite how clean and brilliant they are. The Tardis. a box that's bigger on the inside - such a perfect idea that even J.K. Bowling recycled it for one of her Quidditch tents. Sometimes we've happily re-used old monsters, simply because the old show used archetypes that can't be bettered. Let's face it, any sci-fi adventurer worth his salt is going to encounter a race of evil metal machines at some point, so why discard Terry Nation's wonderful Daleks? (Although we did reinvent their wheels a little bit, and gave them the power of flight.)

At the same time, new ideas and new techniques, such as the wonders of computer graphics, have given us new creatures, new landscapes, new scares which we hope will burn as fiercely as the old.

Now the production team at BBC Wales has finished filming and the 13 new episodes are rolling out of the edit suite, ready to he seen. And we wait. Hopefully, the gaps in production have been hidden a little better, because the old budgetary limitations would be crucified in today's television landscape. But the vital gap still exists - the gap that might allow new children to be filled with wonder - because that gap is built into the format of the series, in the fact that the Tardis can land in the real world. So an eight-year-old can imagine stepping on board. And once on board, the mind can go anywhere.

As for me. I had one perfect opportunity to close the circle, to link my childhood fantasies with the modern image. The shop-window dummies are back, by virtue of the fact that they are, as The Simpsons' Comic Book Guy would say, the Best Idea Ever. And this time, they jerk to life. They step forward. They raise their hands; they chop down. And after 35 years of waiting, finally, the glass shatters. And the screaming starts.

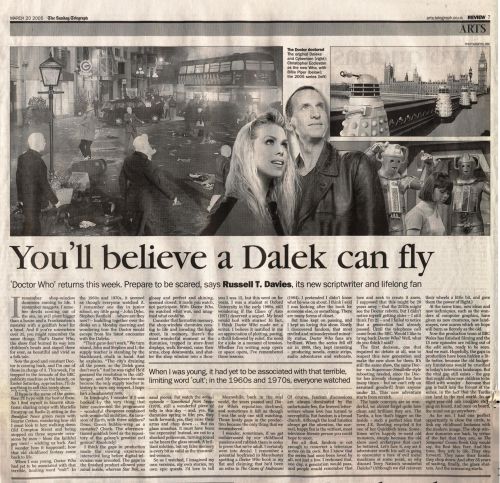

Caption: The Doctor doctored The original Daleks and Cybermen (right); Christopher Eccleston as the new Who, with Billie Piper (below); the 2005 series (left)

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Davies, Russell T. (2005-03-20). You'll believe a Dalek can fly. The Sunday Telegraph (England) p. Review, p. 7.

- MLA 7th ed.: Davies, Russell T.. "You'll believe a Dalek can fly." The Sunday Telegraph (England) [add city] 2005-03-20, Review, p. 7. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Davies, Russell T.. "You'll believe a Dalek can fly." The Sunday Telegraph (England), edition, sec., 2005-03-20

- Turabian: Davies, Russell T.. "You'll believe a Dalek can fly." The Sunday Telegraph (England), 2005-03-20, section, Review, p. 7 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=You'll believe a Dalek can fly | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/You%27ll_believe_a_Dalek_can_fly | work=The Sunday Telegraph (England) | pages=Review, p. 7 | date=2005-03-20 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=4 February 2026 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=You'll believe a Dalek can fly | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/You%27ll_believe_a_Dalek_can_fly | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=4 February 2026}}</ref>