Difference between revisions of "Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction"

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) (Created page with "{{article | publication = Radio Times | file = | px = | height = | width = | date = 2013-11-09 | author = Brian Cox | pages = 22 | language = English | type = | description = ...") |

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{article | {{article | ||

| publication = Radio Times | | publication = Radio Times | ||

| − | | file = | + | | file = 2013-11-09 Radio Times.jpg |

| − | | px = | + | | px = 450 |

| height = | | height = | ||

| width = | | width = | ||

| date = 2013-11-09 | | date = 2013-11-09 | ||

| − | | author = | + | | author = Jonathan Holmes |

| pages = 22 | | pages = 22 | ||

| language = English | | language = English | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

| moreDates = | | moreDates = | ||

| text = | | text = | ||

| + | Professor Brian Cox unravels the truth... | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Science of Doctor Who Thursday 9.00pm BBC2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Is TIME TRAVEL possible? Professor Brian Cox should know. Not only is he a physicist, but in The Science of Doctor Who he gets to pilot the Tardis with the Doctor himself. And the answer is... Yes! (see panel, right, for details) Furthermore, Doctor Who is the best place to start your journey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "I passionately believe we need to get more kids interested in science," says Cox, "and I think good science fiction is a way of getting them interested. When I was seven or eight years old I was just interested in science, and there's no difference between science and science fiction at that age. Why would you be able to tell the difference? It's just something you're interested in:' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cox has fond memories of Doctor Who, which celebrates its 50th anniversary on 23 November, and is looking to ground the show's science fiction in science fact. "Jon Pertwee was my Doctor, and I had a Doctor Who annual telling me the whole history of the Daleks. I love those things. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "From a science-fiction perspective, there's some brilliant writing in the new Doctor Who. And because you're interested in the programme, you're interested in time and space, which might make you want to learn about relativity. I think that's the way it can work, certainly on a younger audience. That's the point of the lecture: to link the themes of Doctor Who straight into actual science." | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is a hint of the Doctor in the way Cox teaches his audience about the possibility of time travel and alien life. Rather than dry facts, he sketches out a madcap universe of wonders, where the theory of relativity is demonstrated by zipping back and forth in a wheely chair (see panel, right) and walking into a black hole results in "spaghettification". | ||

| + | |||

| + | At one point when describing the connection between space and time, he almost lapses into Who jargon. "I'm tempted to say, as the Doctor would, 'wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey: But I won't. (But I just did.)" | ||

| + | |||

| + | While Cox is confident that it's theoretically possible to travel into the future, travelling into the past is a different matter. However, the answer may lie inside the Tardis. "Even if it were possible to travel into the past, we would have to do engineering on the scale of stars, involving things like black holes. Part of the Doctor Who legend is the Heart of the Tardis [the Eye of Harmony], which they call a 'frozen star'. And that's right, it would have to be something like that! Time moves slower and slower as you approach a collapsing star, until it freezes. So a black hole is a frozen star, like the Eye of Harmony." | ||

| + | |||

| + | OF COURSE, DOCTOR Who isn't a textbook. Jon Pertwee's favourite trick was to "reverse the polarity of the neutron flow", a sentence that would give physicists a headache. Instead, Cox hopes the show will inspire children to go into science. If Professor Cox had his own Tardis, he would travel back to scientist Michael Faraday's Christmas lecture of 1860. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Faraday made significant breakthroughs in electromagnetism. Yet in his lectures for children, he patiently explained the chemical processes involved in burning a humble candle. The lectures heavily influenced The Science of Doctor Who, and Cox hopes to have a similar impact: "Faraday inspired a generation of children to become scientists using a simple candle." Travelling back in time might not break the laws of physics, though it would certainly bend them. But that striving for a seemingly impossible goal, that sense of adventure, is the point for Cox. "There's still the faint possibility that someday, maybe a young girl or boy will be inspired to try. Even if they fail, by the very act of trying they might change the world." That's the thing about humans. In a vast universe, we are so much bigger on the inside. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | TIME TRAVEL - HOW IT WORKS | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Brian Cox's lecture for The Science of Doctor Who, physicist Professor Jim Al-Khalili is moved back and forth on stage sitting in a wheelchair in an experiment to show how time is relative... "Our time is personal to us: this is what Einstein discovered - there's no such thing as absolute time," explains Brian Cox. "So why don't we notice this in everyday life? Because the amount by which time slowed down for Jim as he was moving across the stage was minuscule, because the speed he was travelling was so small compared to the speed of light. But if we'd have sent Jim off in a rocket flying out into space... | ||

| + | |||

| + | "Let's say we catapulted Jim off at 99.4 per cent the speed of light for five years, according to his watch. Then we tell Jim to turn round and come back - it takes another five years to get back to the Earth - so for him the journey would take ten years. But for us, with our watches ticking faster than Jim's, 29 years would have passed. Jim would return in 2042 having gauged only ten years. So he'd be a time traveller. Time travel into the future is possible. In fact, it's an intrinsic part of the way the universe is built. We're all time travellers in our own small way." | ||

| + | |||

| + | AND WHERE ARE THE ALIENS? | ||

| + | |||

| + | "Are we alone in the universe? I'd say this is one of the most important questions in modem science. We're on the verge of launching telescopes and detectors so sensitive that we can analyse the light not only from stars but also the light reflected and absorbed by the atmospheres of planets around the stars. This will allow us to look for the fingerprints of molecules such as water, methane and even organic molecules - the fingerprints of life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "These techniques might provide evidence that we're not alone in the universe. These chemical fingerprints won't differentiate between simple single-celled organisms and the complex, multicellular life that is surely a prerequisite for the existence of a civilisation like our own. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "But there is just a possibility that we can look for signatures of intelligent civilisations. As a civilisation gets more and more advanced, its energy consumption rises dramatically. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "Every machine, no matter how sophisticated or efficient, must leave a telltale heat signature behind. Researchers at Penn State University in the USA are attempting to exploit this fundamental universal law, using infrared cameras to search the stars... to see if they can see hot spots, systems that are giving out more heat in the infrared spectrum than you would expect from purely natural processes. Doctor Who from afar!" | ||

| + | |||

| + | Extracted from Thursday's Science of Doctor Who DOCTOR WHO AT 50 | ||

| + | |||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:05, 17 February 2014

- Publication: Radio Times

- Date: 2013-11-09

- Author: Jonathan Holmes

- Page: 22

- Language: English

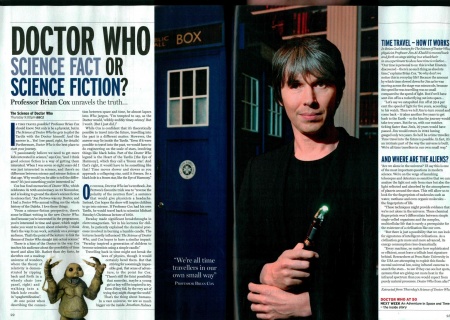

Professor Brian Cox unravels the truth...

The Science of Doctor Who Thursday 9.00pm BBC2

Is TIME TRAVEL possible? Professor Brian Cox should know. Not only is he a physicist, but in The Science of Doctor Who he gets to pilot the Tardis with the Doctor himself. And the answer is... Yes! (see panel, right, for details) Furthermore, Doctor Who is the best place to start your journey.

"I passionately believe we need to get more kids interested in science," says Cox, "and I think good science fiction is a way of getting them interested. When I was seven or eight years old I was just interested in science, and there's no difference between science and science fiction at that age. Why would you be able to tell the difference? It's just something you're interested in:'

Cox has fond memories of Doctor Who, which celebrates its 50th anniversary on 23 November, and is looking to ground the show's science fiction in science fact. "Jon Pertwee was my Doctor, and I had a Doctor Who annual telling me the whole history of the Daleks. I love those things.

"From a science-fiction perspective, there's some brilliant writing in the new Doctor Who. And because you're interested in the programme, you're interested in time and space, which might make you want to learn about relativity. I think that's the way it can work, certainly on a younger audience. That's the point of the lecture: to link the themes of Doctor Who straight into actual science."

There is a hint of the Doctor in the way Cox teaches his audience about the possibility of time travel and alien life. Rather than dry facts, he sketches out a madcap universe of wonders, where the theory of relativity is demonstrated by zipping back and forth in a wheely chair (see panel, right) and walking into a black hole results in "spaghettification".

At one point when describing the connection between space and time, he almost lapses into Who jargon. "I'm tempted to say, as the Doctor would, 'wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey: But I won't. (But I just did.)"

While Cox is confident that it's theoretically possible to travel into the future, travelling into the past is a different matter. However, the answer may lie inside the Tardis. "Even if it were possible to travel into the past, we would have to do engineering on the scale of stars, involving things like black holes. Part of the Doctor Who legend is the Heart of the Tardis [the Eye of Harmony], which they call a 'frozen star'. And that's right, it would have to be something like that! Time moves slower and slower as you approach a collapsing star, until it freezes. So a black hole is a frozen star, like the Eye of Harmony."

OF COURSE, DOCTOR Who isn't a textbook. Jon Pertwee's favourite trick was to "reverse the polarity of the neutron flow", a sentence that would give physicists a headache. Instead, Cox hopes the show will inspire children to go into science. If Professor Cox had his own Tardis, he would travel back to scientist Michael Faraday's Christmas lecture of 1860.

Faraday made significant breakthroughs in electromagnetism. Yet in his lectures for children, he patiently explained the chemical processes involved in burning a humble candle. The lectures heavily influenced The Science of Doctor Who, and Cox hopes to have a similar impact: "Faraday inspired a generation of children to become scientists using a simple candle." Travelling back in time might not break the laws of physics, though it would certainly bend them. But that striving for a seemingly impossible goal, that sense of adventure, is the point for Cox. "There's still the faint possibility that someday, maybe a young girl or boy will be inspired to try. Even if they fail, by the very act of trying they might change the world." That's the thing about humans. In a vast universe, we are so much bigger on the inside.

TIME TRAVEL - HOW IT WORKS

In Brian Cox's lecture for The Science of Doctor Who, physicist Professor Jim Al-Khalili is moved back and forth on stage sitting in a wheelchair in an experiment to show how time is relative... "Our time is personal to us: this is what Einstein discovered - there's no such thing as absolute time," explains Brian Cox. "So why don't we notice this in everyday life? Because the amount by which time slowed down for Jim as he was moving across the stage was minuscule, because the speed he was travelling was so small compared to the speed of light. But if we'd have sent Jim off in a rocket flying out into space...

"Let's say we catapulted Jim off at 99.4 per cent the speed of light for five years, according to his watch. Then we tell Jim to turn round and come back - it takes another five years to get back to the Earth - so for him the journey would take ten years. But for us, with our watches ticking faster than Jim's, 29 years would have passed. Jim would return in 2042 having gauged only ten years. So he'd be a time traveller. Time travel into the future is possible. In fact, it's an intrinsic part of the way the universe is built. We're all time travellers in our own small way."

AND WHERE ARE THE ALIENS?

"Are we alone in the universe? I'd say this is one of the most important questions in modem science. We're on the verge of launching telescopes and detectors so sensitive that we can analyse the light not only from stars but also the light reflected and absorbed by the atmospheres of planets around the stars. This will allow us to look for the fingerprints of molecules such as water, methane and even organic molecules - the fingerprints of life.

"These techniques might provide evidence that we're not alone in the universe. These chemical fingerprints won't differentiate between simple single-celled organisms and the complex, multicellular life that is surely a prerequisite for the existence of a civilisation like our own.

"But there is just a possibility that we can look for signatures of intelligent civilisations. As a civilisation gets more and more advanced, its energy consumption rises dramatically.

"Every machine, no matter how sophisticated or efficient, must leave a telltale heat signature behind. Researchers at Penn State University in the USA are attempting to exploit this fundamental universal law, using infrared cameras to search the stars... to see if they can see hot spots, systems that are giving out more heat in the infrared spectrum than you would expect from purely natural processes. Doctor Who from afar!"

Extracted from Thursday's Science of Doctor Who DOCTOR WHO AT 50

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Holmes, Jonathan (2013-11-09). Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction. Radio Times p. 22.

- MLA 7th ed.: Holmes, Jonathan. "Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction." Radio Times [add city] 2013-11-09, 22. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Holmes, Jonathan. "Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction." Radio Times, edition, sec., 2013-11-09

- Turabian: Holmes, Jonathan. "Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction." Radio Times, 2013-11-09, section, 22 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Doctor_Who:_Science_Fact_or_Science_Fiction | work=Radio Times | pages=22 | date=2013-11-09 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=9 February 2026 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Doctor Who: Science Fact or Science Fiction | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Doctor_Who:_Science_Fact_or_Science_Fiction | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=9 February 2026}}</ref>