The Why of Who

- Publication: London Evening Standard

- Date: 1977-01-31

- Author: Martin Wainwright

- Page: 13

- Language: English

First in a series about London's most popular TV programmes and the scene behind the screen.

IT WASN'T until episode five of a 12-week experimental children's series that BBC TV struck gold. On to the sci-fi set of Dr Who swivelled a tinny-voiced tyrant, grinding out in a chilling monotone its favourite word—"Ex-ter-min-ate."

The Daleks had arrived—and more than 400 weeks of time-travelling, four Dr Whos, nine plucky assistants and hundreds of thousands of pounds earned in sales abroad were on their tail.

Yet walk on to the set of Dr Who today, waving your arms like death rays and muttering that hyphen-fractured catalogue of threats, and you're likely to be booed and told to go home. The time-travellers have got bored with their most famous foes. The present Dr Who thinks the Daleks are dreary. The script editor hasn't much time for them at all. They won't be appearing this year.

Yet Daleks or not, and in spite of the vindictive harrying of the relentless Time Lords, Dr Who sails gaily into its 14th year.

Trapped in a plywood and cardboard sewer, theoretically under the 1890s East End, a Jack-the-Ripperish prostitute patiently allowed herself to be eliminated by the special-effects department two dozen times. A giant rat chatted to a girl with Linda written in yellow sticky tape on her clip-file. A technician walked round holding a tarantula.

High above them, hidden beyond the tangle of cables and TV lights, the executives in the twilit control room cheerfully considered the fantastic goings-on below, discussed the merits of cyanide gas with the Doctor and rapped out mysterious instructions.

" Right, take it from 203, Ros— '... you intellectual fool '." Self-confidence bubbled everywhere. The script editor, puffing away at his pipe, spoke happily of the limitless range of centuries and galaxies his writers are invited to plunder. The designer, Roger Murray-Leach, described his descent into Hammersmith's sewers in search of realism and implied that even Goethe's cool stage directions in Faust (Enter The Lord, followed by the Heavenly Host) would tax neither the inventiveness nor the budget of the series.

The acting was convincing and assured. Tom Baker, the present Doctor, camp to the programme from the National Theatre, and his latest assistant, Louise Jameson, from the Royal Shakespeare Company. It was easy to see that this was a show with all sails bearing, the flagship of a BBC battle squadron.

Broadcasting House is coy about the cost of time-travel, saying its accountancy is so peculiar that figures would be meaningless; but £400,000 has been mentioned as the bill for a series. And on the earnings side, the programme has been sold to 22 foreign countries so far.

Frequently drama's sole representative in the ratings' top 10, Dr Who commands audiences of up to 131 million and this year's average is 2,000,000 up on 1975-76. The names of its defunct rivals on the other channels, Space 1999, Happy Days, New Faces and a dozen others, read like the roll-call on a First World War cenotaph.

Like the cenotaph itself, the Doctor has many of the venerable trappings of an institution. Viewers have seen more than 400 weekly episodes since 1963. Tom Baker, confides Louise Jameson, eats, sleeps and drinks the part, stubbing out his cigarette when button-holed by child fans and spending spare time helping out for charities. There's a Dr Who Appreciation Society which agitates querulously for the return of the Daleks. And when those celebrated monsters do appear, they make you, like fire engines, want to jump up and down and cheer.

Like so many successes, the programme's triumph was quite unforeseen. Originally intended for a 12-week run, it was thought up to fill a gap by two BBC department heads, Sidney Newman and Donald Wilson, and entrusted to a fledgling producer. Verity Lambert.

Enthusiasm was limited to start with, as William Hartnell and his TV grand-daughter Carole Ann Ford took various Aunty-ish and improving trips through history. But then came episode five.

From then on the Daleks' inventor, Terry Nation, reaped an immense harvest in patent rights. For her part, Verity Lambert has risen to become head of drama at Thames, the television world's equivalent of a Time Lord. But how much does their founding inspiration underpin the series' continuing success?

A school of thought exists which holds the Daleks to be the sole master-key on the ring of clues to the popularity of Dr Who. Admittedly the viewers fall for anything and everything — emus, Michael Crawford, Starsky, or is it Hutch? But none match the intensity of the national love affair with these callous tyrants, gliding round their antiseptic control rooms and hiding, as all tyrants hide, a pathetic piece of humanoid debris under their armoured tops.

Gamely the series' authors have dreamed up new monstrosities and others are certain to come, faceless trans-sexual lizards, invisible bloodsucking space gerbils, child-slavers who live on Venus and vote Conservative. But behind them all stands the mocking ghost of the Black Dalek, and he's laughing.

"You aren't a patch on us, and you know it. Exterminate."

But in Studio One, they aren't listening. Tom Baker dismisses the Daleks as " dreary, blundering things, moving on one level and talking on one note." Bob Holmes, the script editor, comments drily: "They aren't great conversationalists." And the programme's new producer, Graham Williams, thinks their battles with the Doctor should be rationed,

"If we had them on four times a season, they'd become boring," he says.

Punctuating these comments are more-revealing phrases in the anti-Dalek catechism—those which refer again and again to the monster's childishness. Symptomatic of a fundamental trend, they mark how gently but deliberately, Dr Who's time-machine is moving into a new adventure—the Planet of the Grown-Ups.

Today, the programme's audience divides 60-40 between adults and children and the showing time, at 6.25, is well out of the hour set aside for kids. At the same time, one of the key characters, the Doctor's assistant, has changed her character remarkably.

Louise Jameson played sweet, innocent roles with the RSC, taking Shakespearian parts like Cordelia. They were much in line with the Doctor's previous accomplices, especially the delightful but accident-prone Lis Sladen, whose Sarah Jane went back from the police box to her summery, tennis-playing suburb last autumn. The new Who girl, Leela, is tough, independent-minded and thigh-revealing.

"Someone in her own right and a bit primitive," says Philip Hinchcliffe, the retiring producer, who chose Louise deliberately to change the part.

"We tried before. Katy Manning had a PhD in the series and Lis Sladen had an exciting job (as a journalist)."

But both settled into the traditional mould of the little-girl buddy of the Doctor. Landed in extremis by his fumbling but always hauled free in the end, they were ideal characters for children to relate to in a series which—for various particular reasons such as contact difficulties but no general ones—has no children in it.

Leela is patently aimed at the Dads, or at least at the over-16s—though this isn't officially fully accepted. Louise Jameson doesn't think the programme is going to lose its children viewers and Mr Hinchcliffe, who, like all the Dr Who people, seems to have a private child consultant, refers to a little girl next door who has told him to make the Doctor's sidekick more independent.

But the new emphasis Is clearly going to draw more exhaustingly on an old ability of the programme—to have it both ways by operating skilfully at two levels. If the Doctor makes his intellectual points, increasingly common and beloved of sci-fi fans, while doing battle with giant rats, both age groups should be content.

The programme's tradition of good humour offers a helping hand. Though the Auntie image may have long since gone, the Doctor remains a sort of Uncle, endearingly inefficient and prone to bungles. Without descending into coy self-parody, the programme deliberately and regularly trips up over itself.

"Tongue-in-cheek," says Philip Hinchcliffe. And Louise Jameson comments: "We're great bumblers."

So far, the humour has failed to draw the fangs of the most-determined attacker of Dr Who, not the black Dalek but Mrs Mary Whitehouse. Often sniped-at for her concentration on sex, Mrs W goes for the Doctor bald-headed over the violence he seems to ignite.

Certainly she hits at one of the programme's most blatant ploys. The Pearl White element of heroines menaced by everything from carniverous delphiniums to railway trains is exceptionally strong. And it is true that the Doctor's Pearls are cast a little carelessly before the programme's swine. Sarah Jane may have regularly scrambled free and Leela fights herself efficiently out of harm's way; but lesser mortals go under by the dozen.

But it's all fantasy—and very clearly so. As Bob Holmes points out, its real strength depends on its inventive reworking of some of the oldest dramatic ideas.

"Everything has become so reallistic nowadays," he says. "The cowboy films, The Sweeney and so on."

Their heroes are all flawed. But in Dr Who, the goodie still wears a white setston, rides into town at the right moment and deals with a really bad baddie in the nick of time.

"All you need," says Bob Holmes, "is a strong, original idea. It doesn't have to be your own strong, original idea."

Which hints—and it's enough to keep thousands watching—that the Daleks will eventually come back.

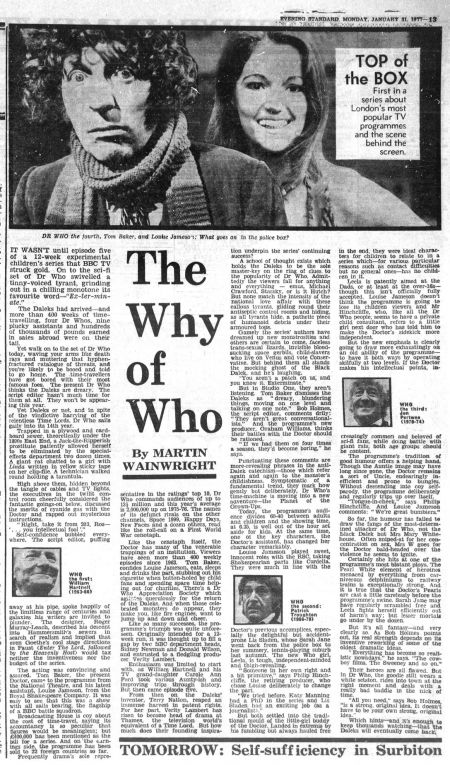

DR WHO the fourth, Tom Baker, and Louise Jamieson: What goes on in the police box?

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Wainwright, Martin (1977-01-31). The Why of Who. London Evening Standard p. 13.

- MLA 7th ed.: Wainwright, Martin. "The Why of Who." London Evening Standard [add city] 1977-01-31, 13. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Wainwright, Martin. "The Why of Who." London Evening Standard, edition, sec., 1977-01-31

- Turabian: Wainwright, Martin. "The Why of Who." London Evening Standard, 1977-01-31, section, 13 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=The Why of Who | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Why_of_Who | work=London Evening Standard | pages=13 | date=1977-01-31 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=8 February 2026 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=The Why of Who | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Why_of_Who | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=8 February 2026}}</ref>