Henry Woolf

- Publication: The Times

- Date: 2021-11-24

- Author:

- Page: 57

- Language: English

Actor whose collaborations with his old friend Harold Pinter included directing his first play and providing a bedsit for his assignations

Henry Woolf was on a theatre-directing course at the University of Bristol in the 1950s when he met up with an old schoolfriend for a cup of tea. Harold Pinter, then a freshly married actor toiling impecuniously on the repertory circuit, told him of being taken to a party in Chelsea by an actress, who invited him to meet the man who lived upstairs. This turned out to be the writer Quentin Crisp, who was barefoot and wearing flamboyant clothes. They discussed everything from philosophy to the weather as Crisp served tea, bacon and eggs to an enormous man who was sitting silently at the table wearing a cap and reading a comic.

Pinter (obituary, December 26, 2008) was thinking of writing a play based on the incident; Woolf knew that his course leaders in Bristol were looking for low-budget, one-act works. He told the drama department that his friend had written a brilliant play that could be staged for one shilling. When they agreed, he told Pinter to get writing. "Harold said he couldn't do it in less than six months," Woolf told The Jewish Chronicle. "But he did it in two days. He says it was four, but he is wrong."

In The Room (1957), which was Pinter's first play, Woolf played the landlord Mr Kidd. He described how the production changed British theatre. "On the first night the audience woke up from its polite cultural stupor and burst into unexpected life, laughing, listening, taking part in the story unfurling -on stage:' he said. "They had just been introduced to Pinterland, where no explanations are offered, no quarter given, and you have the best time in theatre you've ever had in your life." However, he had been wrong about it costing only one shilling. "The stage manager was in love with the actor who was supposed to be given bread," he said. "But she fed him eggs and bacon and the costs went up to four shillings and six- pence."

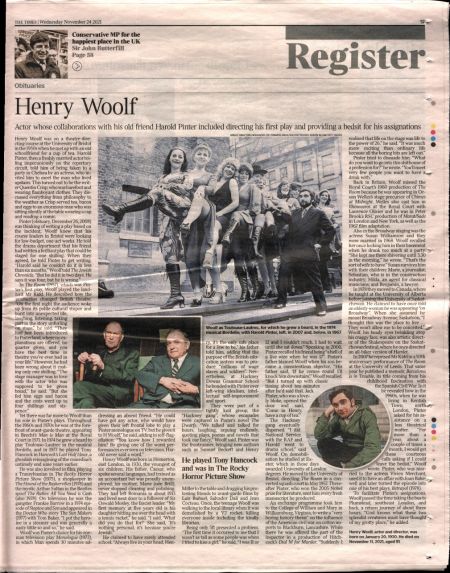

Yet there was far more to Woolf than his role in Pinter's plays. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s he was at the forefront of avant-garde theatre, appearing in Brecht's Man is Man at the Royal Court in 1971. In 1974 he grew a beard to play Toulouse-Lautrec in the musical Bordello, and in 1977 he played Tony Hancock in Hancock's Last Half Hour, a ghoulish reimagining of the comedian's untimely end nine years earlier.

He was also involved in film, playing a Transylvanian in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), a shopkeeper in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1978) and the mystic Arthur Sultan in the Beatles spoof The Rutles: All You Need is Cash (also 1978). On television he was the gangster Frankie Barrow in a 1974 episode of Steptoe and Son and appeared in the Doctor Who story The Sun Makers (1977) with Tom Baker. "I put the heroine in a steamer and was generally a nasty little so and so," he said.

Woolf was Pinter's choice for his one-man television play Monologue (1973), in which Man spends 30 minutes addressing an absent friend. "He could have got any actor, who would have given their left frontal lobe to play a Pinter monologue on TV, but he gives it to H Woolf," he said, adding in self-flagellation: "You know how I rewarded him? By giving one of the worst performances ever seen on television. Harold never said a word."

Henry Woolf was born in Homerton, east London, in 1930, the youngest of six children. His father, Caesar, who spoke several languages, had trained as an accountant but was proudly unemployed; his mother, Marie (née Brill), never stopped cleaning and polishing. They had left Romania in about 1913 and lived next door to a follower of Sir Oswald Mosley, the fascist leader. "My first memory at five years old is his daughter hitting me over the head with a tennis racket," he said. "I said, 'What did you do that for?' She said, 'It's nothing personal, it's because you're Jewish'."

He claimed to have rarely attended school. "Always live in your head, Henry, it's the only safe place for a Jew to be," his father told him, adding that the purpose of the British education system was to produce "millions of wage slaves and soldiers". Nevertheless, at Hackney Downs Grammar School he bonded with Pinter over left-wing idealism, intellectual self-improvement and sport.

They were part of a tightly knit group, the "Hackney gang", whose escapades were captured in Pinter's novel The Dwarfs. "We talked and talked for hours, laughing, arguing endlessly quoting plays, poems and novels that took our fancy," Woolf said. Pinter was the frontrunner, bringing new author such as Samuel Beckett and Henry Miller to the table and dragging his protesting friends to avant-garde films by Luis Builuel, Salvador Dali and Jean Cocteau. Once, the teenage Woolf was walking to the local library when it was demolished by a V2 rocket, killing everyone inside including the kindly librarian.

Being only 5ft presented a problem. "The first time it occurred to me that I wasn't as tall as some people was when I tried to kiss a girl," he said. "I was 11 or 12 and I couldn't reach. I had to wait until she sat down." Speaking in 2000, Pinter recalled his friend being "a hell of a live wire when he was 17". Pinter's father blamed Woolf when his son became a conscientious objector. "His father said, 'If he comes round I'll knock him downstairs'," Woolf recalled. "But I turned up with classic

timing about ten minutes after he'd said that. Jack Pinter, who was a lovely bloke, opened the door and said, 'Come in Henry, have a cup of tea'." The Hackney gang eventually dispersed. "I did National Service with the RAF and Harold went to drama school," said Woolf. On demobilisation he studied at Exeter, which in those days awarded University of London degrees. He moved to the University of Bristol, directing The Room in a converted squash court in May 1957. Thereafter Pinter, who won the 2005 Nobel prize for literature, sent him every fresh manuscript he produced.

An exchange programme took him to the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, to write a "very boring history thesis" on the influence of the American civil war on cotton imports to Blackburn, Lancashire. While there he was offered the part of the inspector in a production of Hitch-cock's Dial M for Murder. "Suddenly I realised that life on the stage was life to

the power of 26," he said. "It was much more exciting than ordinary life because all the boring bits are left out."

Pinter tried to dissuade him. "What do you want to go into this shithouse of a profession for?" he wrote. "You'll meet very few people you want to have drink with."

Back in Britain, Woolf missed the Royal Court's 1960 production of The Room because he was appearing in Orson Welles's stage precursor of Chimes at Midnight. Welles also cast him in Rhinoceros at the Royal Court with Laurence Olivier and he was in Peter Brook's RSC production of Marat/Sade in London and New York, as well as the 1967 film adaptation.

Also in the Broadway staging was the actress Susan Williamson and they were married in 1968. Woolf recalled her once locking him in their basement when he drank too much at a party. "She kept me there shivering until 3.30 in the morning," he wrote. "That's the sort of wife to have." Susan survives him with their children: Marie, a journalist; Sebastian, who is in the construction industry; Hilda, an agent for classical musicians; and Benjamin, a lawyer.

In 1978 they moved to Canada, where he taught at the University of Alberta before joining the University of Saskatchewan. He claimed to have once told an elderly woman he was appearing "on Broadway". When she assumed he meant Broadway Avenue, Saskatoon, "I thought this was the place to live ... They won't allow me to be conceited." Woolf, his beady eyes twinkling atop his craggy face, was also artistic director of the Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan festival, where he once directed an all-biker version of Hamlet.

In 2007 he reprised Mr Kidd in a 50th anniversary performance of The Room at the University of Leeds. That same year he published a memoir, Barcelona is in Trouble, its title coming from his childhood fascination with the Spanish Civil War. In it he revealed how in the 1960s, when he was living in Kentish Town, north London, Pinter asked for his assistance on a less theatrical matter. "For more than a year, about a couple of times a month, I would get these courteous calls asking if I could leave the bedsit," Woolf wrote. Pinter, who was married to the actress Vivien Merchant, used it to have an affair with Joan Bakewell and later turned the episode into " one of his best plays, Betrayal (1978).

To facilitate Pinter's assignations, Woolf passed the time taking the bus to Plumstead, southeast London, and back, a return journey of about three hours. "God knows what these two splendid creatures must have thought of my grotty place," he added.

Henry Woolf, actor and director, was born on January 20, 1930. He died of November 11, 2021, aged 91

Caption: Woolf as Toulouse-Lautrec, for which he grew a beard, in the 1974 musical Bordello; with Harold Pinter, left, in 2007 and, below, in 1967

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: (2021-11-24). Henry Woolf. The Times p. 57.

- MLA 7th ed.: "Henry Woolf." The Times [add city] 2021-11-24, 57. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: "Henry Woolf." The Times, edition, sec., 2021-11-24

- Turabian: "Henry Woolf." The Times, 2021-11-24, section, 57 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Henry Woolf | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Henry_Woolf | work=The Times | pages=57 | date=2021-11-24 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=15 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Henry Woolf | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Henry_Woolf | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=15 December 2025}}</ref>