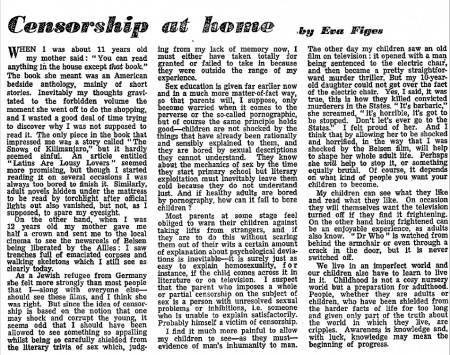

Censorship at home

- Publication: The Guardian

- Date: 1967-12-11

- Author: Ewes Pities

- Page: 4

- Language: English

WHEN I was about 11 years old my mother said: " You can read anything in the house except that book." The book she meant was an American bedside anthology, mainly of short stories. Inevitably my thoughts gravitated to the forbidden volume the moment she went off to do the shopping, and I wasted a good deal of time trying to discover why I was not supposed to read it. The only piece in the book that impressed me was a story called " The Snows of Kilimanjaro," but it hardly seemed sinful. An article entitled "Latins Are Lousy Lovers " seemed more promising, but though I started reading it on several occasions I was always too bored to finish it, Similarly, adult novels hidden under the mattress to be read by torchlight after official lights out also vanished, but not, as I supposed, to spare my eyesight.

On the other hand, when I was 12 years old my mother gave me half a crown and sent me to the local cinema to see the newsreels of Belsen being liberated by the Allies : I saw trenches full of emaciated corpses and walking skeletons which I still see as clearly today.

As a Jewish refugee from Germany she felt more strongly than most people that I—along with everyone else—should see these films, and I think she was right. But since the idea of censorship is based on the notion that one may shock and corrupt the young, it seems odd that I should have been allowed to see something so appalling whilst being so carefully shielded from the literary trivia of sex which, judging from my lack of memory now, I must either have taken totally for granted or failed to take in because they were outside the range of my experience.

Sex education is given far earlier now and in a much more matter-of-fact way, so that parents will, I suppose, only become worried when it comes to the perverse or the so-called pornographic, but of course the same principle holds good—children are not shocked by the things that have already been rationally and sensibly explained to them, and they are bored by sexual descriptions they cannot understand. They know about the mechanics of sex by the time they start primary school but literary exploitation must inevitably leave them cold because they do not understand lust. And if healthy adults are bored by pornography, how can it fail to bore children ?

Most parents at some stage feel obliged to warn their children against taking lifts from strangers, and if they are to do this without scaring them out of their wits a certain amount of explanation about psychological deviations is inevitable—it is surely just as easy to explain homosexuality, f o r instance, if the child comes across it in literature or on television. I suspect that the parent who imposes a whole or partial censorship on the subject of sex is a person with unresolved sexual problems or inhibitions, i.e. someone who is unable to explain satisfactorily. Probably himself a victim of censorship,

I find it much more painful to allow my children to see—as they must—evidence of man's inhumanity to man. The other day my children saw an old film on television : it opened with a man being sentenced to the electric chair:, and then became a pretty straightforward murder thriller. But my 10-year-old daughter could not get over the fact of the electric chair. Yes, I said, it was true, this is how they killed convicted murderers in the States. "It's barbaric," she screamed, " it's horrible, it's got to be stopped. Don't let's ever go to the States." I felt proud of her. And I think that by allowing her to be shocked and horrified, in the way that I was shocked by the Belsen film, will help to shape her whole adult life. Perhaps she will help to stop it, or something equally brutal. Of course, it depends on what kind of people you want your children to become.

My children can see what they like and read what they like. On occasion they will themselves want the television turned off if they find it frightening. On the other hand being frightened can be an enjoyable experience, as adults also know. " Dr Who " is watched from behind the armchair or even through a crack in the door, but it is never switched off.

We live in an imperfect world and our children also have to learn to live in it. Childhood is not a cosy nursery world but a preparation for adulthood. People, whether they are adults or children, who have been shielded from the harder facts of life for too long and given only part of the truth about the world in which they live, are cripples. Awareness is knowledge and, with luck, knowledge may mean the beginning of progress.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Pities, Ewes (1967-12-11). Censorship at home. The Guardian p. 4.

- MLA 7th ed.: Pities, Ewes. "Censorship at home." The Guardian [add city] 1967-12-11, 4. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Pities, Ewes. "Censorship at home." The Guardian, edition, sec., 1967-12-11

- Turabian: Pities, Ewes. "Censorship at home." The Guardian, 1967-12-11, section, 4 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Censorship at home | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Censorship_at_home | work=The Guardian | pages=4 | date=1967-12-11 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 February 2026 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Censorship at home | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Censorship_at_home | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 February 2026}}</ref>