The Climate for Experiment

- Publication: Tatler

- Date: 1965-05-12

- Author: J. Roger Baker

- Page: 320

- Language: English

Artists and people concerned with the social scene are induced to experiment when century moves faster than to do. It happened in the 17th ...

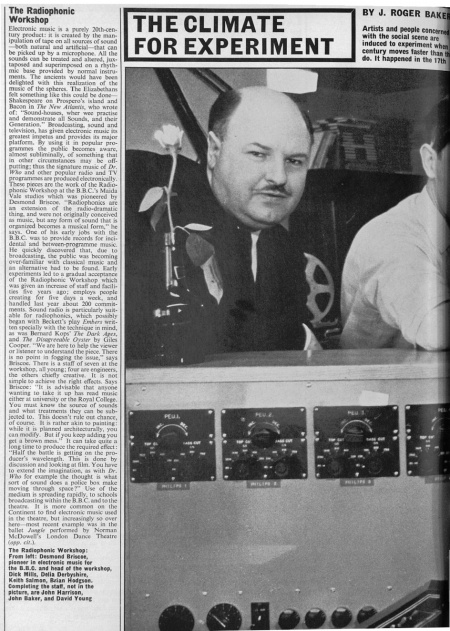

Electronic music is a purely 20th-century product: it is created by the manipulation of tape on all sources of sound —both natural and artificial—that can be picked up by a microphone. All the sounds can be treated and altered, juxtaposed and superimposed on a rhythmic base provided by normal instruments. The ancients would have been delighted with this realization of the music of the spheres. The Elizabethans felt something like this could be done—Shakespeare on Prospero's island and Bacon in The New Atlantis, who wrote of: "Sound-houses, wher wee practise and demonstrate all Sounds, and their Generation." Broadcasting, sound and television, has given electronic music its greatest impetus and provides its major platform. By using it in popular programmes the public becomes aware, almost subliminally, of something that in other circumstances may be off-putting; thus the signature music of Dr. Who and other popular radio and TV programmes are produced electronically. These pieces are the work of the Radio-phonic Workshop at the B.B.C.'s Maida Vale studios which was pioneered by Desmond Briscoe. "Radiophonics are an extension of the radio-dramatic thing, and were not originally conceived as music, but any form of sound that is organized becomes a musical form," he says. One of his early jobs with the B.B.C. was to provide records for incidental and between-programme music. He quickly discovered that, due to broadcasting, the public was becoming over-familiar with classical music and an alternative had to be found. Early experiments led to a gradual acceptance of the Radiophonic Workshop which was given an increase of staff and facilities five years ago; employs people creating for five days a week, and handled last year about 200 commitments. Sound radio is particularly suitable for radiophonics, which possibly began with Beckett's play Embers written specially with the technique in mind, as was Bernard Kops' The Dark Ages, and The Disagreeable Oyster by Giles Cooper. "We are here to help the viewer or listener to understand the piece. There is no point in fogging the issue," says Briscoe. There is a staff of seven at the workshop, all young; four are engineers, the others chiefly creative. It is not simple to achieve the right effects. Says Briscoe: "It is advisable that anyone wanting to take it up has read music either at university or the Royal College. You must know the source of sounds and what treatments they can be subjected to. This doesn't rule out chance, of course. It is rather akin to painting: while it is planned architecturally, you can modify. But if you keep adding you get a brown mess." It can take quite a long time to produce the required effect: "Half the battle is getting on the producer's wavelength. This is done by discussion and looking at film. You have to extend the imagination, as with Dr. Who for example the thought is what sort of sound does a police box make moving through space ?" Use of the medium is spreading rapidly, to schools broadcasting within the B.B.C. and to the theatre. It is more common on the Continent to find electronic music used in the theatre, but increasingly so over here—most recent example was in the ballet Jungle performed by Norman McDowell's London Dance Theatre (opp. cit.).

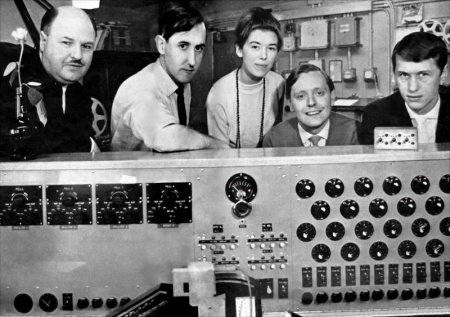

The Radiophonic Workshop: From left: Desmond Briscoe, pioneer in electronic music for the B.B.C. and head of the workshop, Dick Mills, Delia Derbyshire, Keith Salmon, Brian Hodgson. Completing the staff, not in the picture, are John Harrison, John Baker, and David Young

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Baker, J. Roger (1965-05-12). The Climate for Experiment. Tatler p. 320.

- MLA 7th ed.: Baker, J. Roger. "The Climate for Experiment." Tatler [add city] 1965-05-12, 320. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Baker, J. Roger. "The Climate for Experiment." Tatler, edition, sec., 1965-05-12

- Turabian: Baker, J. Roger. "The Climate for Experiment." Tatler, 1965-05-12, section, 320 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=The Climate for Experiment | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Climate_for_Experiment | work=Tatler | pages=320 | date=1965-05-12 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=18 April 2024 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=The Climate for Experiment | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_Climate_for_Experiment | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=18 April 2024}}</ref>