Douglas Adams obituary (The Times)

- Publication: The Times

- Date: 2001-05-14

- Author:

- Page: 17

- Language: English

Douglas Adams, author, was born in Cambridge on March 11, 1952. He died of a heart attack on May 11, 2001, aged 49.

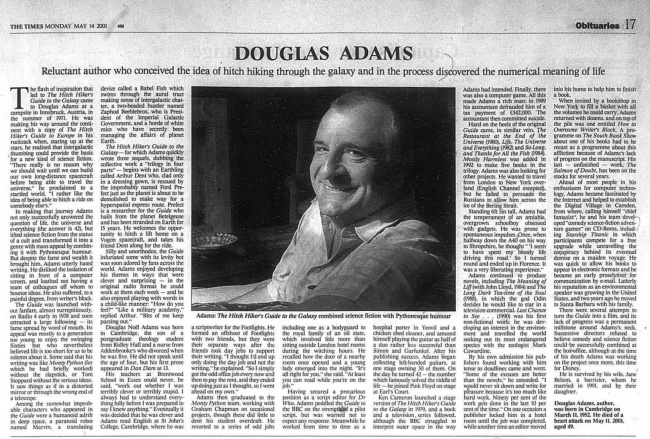

Reluctant author who conceived the idea of hitch hiking through the galaxy and in the process discovered the numerical meaning of life.

The flash of inspiration that led to The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy came to Douglas Adams at a campsite in Innsbruck, Austria, in the summer of 1971. He was making his way around the continent with a copy of The Hitch Hiker's Guide to Europe in his rucksack when, staring up at the stars, he realised that intergalactic thumbing could pro-vide the basis for a new kind of science fiction. "There really is no reason why we should wait until we can build our own long-distance spacecraft before being able to travel the universe," he proclaimed to a startled world. "I rather like the idea of being able to hitch a ride on somebody else's."

In making that journey Adams not only successfully answered the question of life, the universe and everything (the answer is 42), but lifted science fiction from the status of a cult and transformed it into a genre with mass appeal by combining it with Pythonesque humour. But despite the fame and wealth it brought him, Adams utterly hated writing. He disliked the isolation of sitting in front of a computer screen, and loathed not having a team of colleagues off whom to bounce ideas. He also suffered, to a painful degree, from writer's block.

The Guide was launched without fanfare, almost surreptitiously, on Radio 4 early in 1978 and soon attracted a large following - its fame spread by word of mouth. Its appeal was mostly to a generation too young to enjoy the swinging Sixties but who nevertheless believed life is too short for us to be solemn about it. Some said that his writing was like Monty Python (for which he had briefly worked) without the slapstick, or Tom Stoppard without the serious ideas. It saw things as if in a distorted mirror or through the wrong end of a telescope.

Among the somewhat improbable characters who appeared in the Guide were a humanoid adrift in deep space, a paranoid robot named Marvin, a translating device called a Babel Fish which swims through the aural tract making sense of intergalactic chatter, a two-headed hustler named Zaphod Beeblebrox, who is President of the Imperial Galactic Government, and a horde of white mice who have secretly been managing the affairs of planet Earth.

The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy - for which Adams quickly wrote three sequels, dubbing the collective work a "trilogy in four parts" - begins with an Earthling called Arthur Dent who, clad only in a dressing gown, is rescued by the improbably named Ford Prefect just as the planet is about to be demolished to make way for a hyperspatial express route. Prefect is a researcher for the Guide who hails from the planet Betelgeuse and has been stranded on Earth for 15 years. He welcomes the opportunity to hitch a lift home on a Vogon spacecraft, and takes his friend Dent along for the ride.

Silly and unorthodox, the Guide infuriated some with its levity but was soon adored by fans across the world. Adams enjoyed developing his themes in ways that were clever and surprising - in the original radio format he could work at them each week - and he also enjoyed playing with words in a child-like manner: "How do you feel?" "Like a military academy," replied Arthur. "Bits of me keep passing out."

Douglas Noel Adams was born in Cambridge, the son of a postgraduate theology student from Ridley Hall and a nurse from Addenbrooke's who divorced when he was five. He did not speak until the age of four, but his first prose appeared in Dan Dare at 13.

His teachers at Brentwood School in Essex could never, he said, "work out whether I was terribly clever or terribly stupid. I always had to understand everything fully before I was prepared to say I knew anything." Eventually it was decided that he was clever and Adams read English at St John's College, Cambridge, where he was a scriptwriter for the Footlights. He formed an offshoot of Footlights with two friends, but they went their separate ways after the friends took day jobs to support their writing. "I thought I'd end up only doing the day job and not the writing," he explained. "So I simply got the odd office job every now and then to pay the rent, and they ended up doing just as I thought, so I went ahead on my own."

Adams then graduated to the Monty Python team, working with Graham Chapman on occasional projects, though these did little to dent his student overdraft. He resorted to a series of odd jobs including one as a bodyguard to the royal family of an oil state, which involved litle more than sitting outside London hotel rooms during the witching hours. He recalled how the door of a nearby room once opened and a young lady emerged into the night. "It's all right for you," she said. "At least you can read while you're on the job."

Having secured a precarious position as a script editor for Dr Who, Adams peddled the Guide to the BBC on the strength of a pilot script, but was warned not to expect any response. Meanwhile he worked from time to time as a hospital porter in Yeovil and a chicken shed cleaner, and amused himself playing the guitar as half of a duo rather less successful than Simon and Garfunkel. After his publishing success, Adams began collecting left-handed guitars, at one stage owning 30 of them. On the day he turned 42 - the number which famously solved the riddle of life - he joined Pink Floyd on stage at Earl's Court.

Ken Cameron launched a stage version of The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy in 1979, and a book and a television series followed, although the BBC struggled to interpret outer space in the way Adams had intended. Finally, there was also a computer game. All this made Adams a rich man: in 1989 his accountant defrauded him of a tax payment of Pounds 342,000. The accountant then committed suicide.

Hard on the heels of the original Guide came, in similar vein, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980), Life, The Universe and Everything (1982) and So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (1984). Mostly Harmless was added in 1992 to make five books in the trilogy. Adams was also looking for other projects. He wanted to travel from London to New York overland (English Channel excepted), but he failed to persuade the Russians to allow him across the ice of the Bering Strait.

Standing 6ft 5in tall, Adams had the temperament of an amiable, overgrown schoolboy obsessed with gadgets. He was prone to spontaneous impulses. Once, when halfway down the A40 on his way to Shropshire, he thought " 'I seem to have spent my bloody life driving this road.' So I turned round and ended up in Florence. It was a very liberating experience."

Adams continued to produce novels, including The Meaning of Liff (with John Lloyd, 1984) and The Long Dark Tea-time of the Soul (1988), in which the god Odin decides he would like to star in a television commercial. Last Chance to See...(1990) was his first non-fictional work: he was developing an interest in the environment and travelled the world seeking out its most endangered species with the zoologist Mark Cawardine.

By his own admission his publishers found working with him tense as deadlines came and went. "Some of the excuses are better than the novels," he conceded. "I would never sit down and write for pleasure because it's too much like hard work. Ninety per cent of the work gets done in the last 10 per cent of the time." On one occasion a publisher locked him in a hotel room until the job was completed, while another time an editor moved into his home to help him to finish a book.

When invited by a bookshop in New York to fill a basket with all the volumes he could carry, Adams returned with dozens, and on top of the pile was one entitled How to Overcome Writer's Block. A programme on The South Bank Show about one of his books had to be recast as a programme about this affliction because of Adams's lack of progress on the manuscript. His last - unfinished - work, The Salmon of Doubt, has been on the stocks for several years.

Ahead of most people in his enthusiasm for computer technology, Adams became fascinated by the Internet and helped to establish the Digital Village in Camden, from where, calling himself "chief fantasist", he and his team developed "comedy science-fiction adventure games" on CD-Roms, including Starship Titanic in which participants compete for a free upgrade while unravelling the conspiracy behind its eventual demise on a maiden voyage. He was quick to allow his books to appear in electronic formats and he became an early proselytiser for communication by e-mail. Latterly his reputation as an environmental speaker was growing in the United States, and two years ago he moved to Santa Barbara with his family.

There were several attempts to turn the Guide into a film, and its lack of progress was a permanent millstone around Adams's neck. Successive directors refused to believe comedy and science fiction could be successfully combined at the box-office, although at the time of his death Adams was working on the project once more, this time for Disney.

He is survived by his wife, Jane Belson, a barrister, whom he married in 1991, and by their daughter.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: (2001-05-14). Douglas Adams obituary (The Times). The Times p. 17.

- MLA 7th ed.: "Douglas Adams obituary (The Times)." The Times [add city] 2001-05-14, 17. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: "Douglas Adams obituary (The Times)." The Times, edition, sec., 2001-05-14

- Turabian: "Douglas Adams obituary (The Times)." The Times, 2001-05-14, section, 17 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Douglas Adams obituary (The Times) | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Douglas_Adams_obituary_(The_Times) | work=The Times | pages=17 | date=2001-05-14 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=26 April 2024 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Douglas Adams obituary (The Times) | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Douglas_Adams_obituary_(The_Times) | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=26 April 2024}}</ref>