Music for Doctor Who - and you?

- Publication: The Leicester Chronicle

- Date: 1972-05-05

- Author: Pete Barraclough

- Page: 28

- Language: English

THERE'S no subject guaranteed to cause more bitter debate and intolerance than music. Lovers of classical decry pop fans, chamber music enthusiasts listen to nothing but their beloved Vivaldi and Co., and avant garde jazzers wouldn't be seen dead inside the convivial confines of a folk club.

Music certainly is a case of one man's meat, another's poison. But must it always be like that? Terence Dwyer, senior lecturer in music at Loughborough College of Art and Design, feels it's a great pity that people aren't more broadminded.

He's currently involved with the fascinating field of electronic music — a genre that really reflects today's scientific orientated world and exploits modern technology.

To most people its either a discordant, unharmonious noise or that haunting refrain from Doctor Who, but Mr. Dwyer believes It to be potentially one of the most creative forms of modern music.

He visually smarts if you suggest his interest is purely academic and says that he's become involved simply to broaden his musical outlook.

Although electronic music may seem a recent development, in fact it's been around for 20 years in one form or another, but has only been fully exploited In the last decade.

"For ten years composers had rather crude gadgetry" he added. "They used tape recorders and other basic equipment. But then In the Sixties along came the synthesizer and revolutionised the whole field."

The Synthesiser is essentially a smallish computer which the lecturer describes as "an integrated collection of electronic devices for producing sounds and controlling them."

So engrossed is he in this music of the future that he's had a costly synthesiser installed in his own home In Lough. borough Road, Quorn, turning his lounge into something resembling a Cape Kennedy control room with numerous dials and switches.

Despite his dislike of electronic music's Doctor Who image Mr. Dwyer recently visited the BBC's Radiophonic Workshop in London where the ten strong staff have the services of one of the biggest and most complex computer synthesisers in the world, which produces all those eerie sound effects for thriller serials, space films and Apollo moon 'specials.'

However he feels that the men who work the dials at the Workshop aren't really contributing to the field and are 'more craftsmen than composers."

Mr. Dwyer agrees that electronic music is "lacking." Somehow it is too clinical, too perfect and it is this absence of "human" warmth that frightens many people away.

"Those in the electronic music field recognise this and there have even been attempts to write man's imperfections into the programmes of computer synthesisers.

"It's also true that there's something terribly artificial shout audiences sitting down in the Festival Hall for concert of electronic mull and then staring vacantly a speakers all evening.

"I suspect that electronic music will best be used in combination with something live," he added. "There ha been an attempt at electronic ballet, but I would love to see opera with the participants singing to a backing of electronic music."

The lecturer refutes any suggestion that composing with computers is less creative than normal writing. In fact he thinks It's more so because people writing normal orchestral pieces at least know just what sounds they hope to produce. This isn't the case with electronic music.

"The ironical thing about the Synthesiser is that it was Initially invented to Imitate the sounds of ordinary instruments. But this was quickly found to be pointless," he explained.

"With the synthesiser we can now produce any sound we want, even completely new ones. In fact composing limited only by the imagination."

Mr. Dwyer feels that musique concrete Is the ideal compromise between electronic and normal music. Developed by a Frenchman in the Fifties, its fundamentally a way of distorting everyday sounds by electronic means.

The Quorn man recently had a book published on this particular subject and in it he reveals how anyone with a tape recorder or two can quickly became an exponent of the style. All you do is record sounds In the home, and then simply change them by reversing the tape, speeding it up and so on.

Terence Dwyer understands the reason for the Radio One syndrome, even if he finds it a rather depressing situation.

"After all I'm a professional and have spent most of my life studying and appreciating different types of music. As a result I've had to sacrifice things like sport and so on. But it's harder for the man In the street."

There was a time when he too had strong musical prejudices but during his stay at the college he's learned to accept all kinds.

"The students I teach naturally like a wide range of music," he explained. "And so I've grown to appreciate everything from medieval to electronic."

Music is nearly as old as Man himself, and Terry Dwyer supports the thinking of those anthropologists who suggest that It may well be older than speech.

"Don't you think that prehistoric man would have started to croon before he learned to communicate by talking." he added. "After all speech Is a highly developed thing."

For hundreds of years songs and melodies were handed down from father to son and perpetuated In folklore by wandering minstrels. But it's not known just when the first music was written down, although the Chinese were doing Just that more than three thousand years ago.

Down the ages music has become increasingly sophisticated, but Terry Dwyer believes that generally speaking the vast majority always prefer the simpler tunes.

He's convinced that music has evolved in this manner with most people having an inherent ability to memorise and whistle easy melodies. But at the same time there has always been an elite — the musical intellectuals —ever ready to push forward the frontiers.

Thanks to their efforts standards have been raised but he thinks there's now a tremendous gulf between the professionals and the public.

"Contemporary musicians find themselves in a difficult position because they want to experiment for reasons of self-satisfaction, yet the vast majority of the public still want something simple."

As to electronic music, he feels it's vitally important that people accept sounds themselves as beautiful even if they aren't made musical instruments.

"After all, just what is music? If a person finds that a particular sound is enjoyable then to him it's music. It doesn't always have to be sweeping violins."

Captions: The electronic theme for the "Dr. Who" series and the other "way out" music used for this programme could truly be the music of the future.

The electronic music which accompanies the moon men's exploits is potentially "creative" says Terence Dwyer.

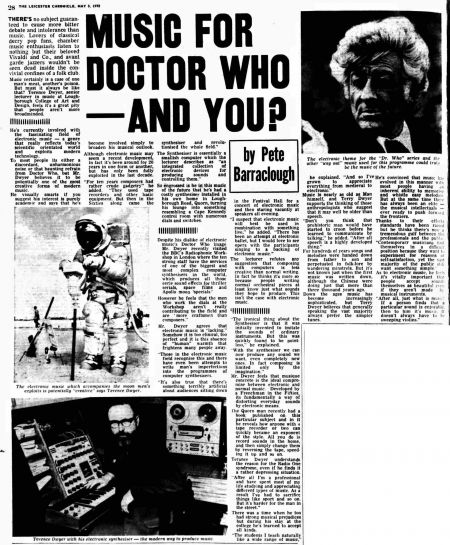

Terence Dwyer with his electronic synthesizer - the modern way to produce music.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Barraclough, Pete (1972-05-05). Music for Doctor Who - and you?. The Leicester Chronicle p. 28.

- MLA 7th ed.: Barraclough, Pete. "Music for Doctor Who - and you?." The Leicester Chronicle [add city] 1972-05-05, 28. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Barraclough, Pete. "Music for Doctor Who - and you?." The Leicester Chronicle, edition, sec., 1972-05-05

- Turabian: Barraclough, Pete. "Music for Doctor Who - and you?." The Leicester Chronicle, 1972-05-05, section, 28 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Music for Doctor Who - and you? | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Music_for_Doctor_Who_-_and_you%3F | work=The Leicester Chronicle | pages=28 | date=1972-05-05 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=22 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Music for Doctor Who - and you? | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Music_for_Doctor_Who_-_and_you%3F | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=22 December 2025}}</ref>