The lost geniuses of library music

- Publication: The Guardian

- Date: 2008-08-29

- Author: Jude Rogers

- Page: 7

- Language: English

They were asked to provide jingles for adverts and schools TV - instead they invented a new world of sound. Jude Rogers on electronic music's secret pioneers

For the past decade, the most sought after vintage musical rarities haven't just been old Northern Soul 45s, or original garage punk singles, or any of the kinds of music that have been compiled into multiple box sets, or whose prime movers' stories of drugs and disasters have been told again and again. Joining the likes of the 13th Floor Elevators in the cult music pantheon have been records made in the 1960s and 7os by often unknown musicians, to be used as incidental music by film, television and radio companies. Many of them are exhilaratingly inventive, but for years they have sat forgotten on dusty shelves. This summer, you can't move for reissues of them.

Why are listeners responding to this old, near-forgotten music, which was never intended for widespread release? John Cavanagh, the Glaswegian boss of the Glo Spot label, which has been reissuing library music, has a theory. "There's a striking originality to library records from that time because they were all about the search for new sounds. Back then, musicians weren't told what to do. Big companies also weren't so obsessed with focus groups and demographics, so musicians were allowed to have more open-ended adventures." The result is music that sounds like nothing else.

This summer's Glo Spot release is Electrosound by Ron Geesin, the composer best known for cowriting Pink Floyd's 1970 album Atom Heart Mother and for being a regular guest on John Peel's early shows. Electrosound was originally made for KPM, the international library label that spawned the theme tunes for Mastermind, News At Ten and Whicker's World, but this record is nothing like those. After all, it features tape manipulations of detuned mandolins and banjos, cymbals played by bows, and the sound of Geesin shouting into the piano.

Geesin still writes in the same converted garage in which he made Electrosound in 1972, and he remembers his experiments fondly. "In those, days it was all about tape, and tape seemed to offer endless possibilities. It released people like me because you could make these strange combinations of the past and the future when you played with it. And because the sounds you could make from it sounded so striking, people from TV wanted to fill their trousers with it."

Geesin wrote jagged piano jingles for Fenzig headache tablets, music for the BBC's Omnibus, and reams of work for schools TV, although his work was occasionally considered too experimental. Take the manipulated flute and bassoon piece he wrote for Rowntree's Wine Gums — the confectioner had asked him to write something new. "They said, 'Not as new as that, Ron!' So I calmed it down and added some banjo, and they said, 'Not as new as that either!"

Lots of library music from this time still sounds futuristic and mind-expanding. In some ways, it recalls the psychedelic music of the same period, and in others acts an aural reminder of the age of space ? travel, when film and TV companies wanted strange music to soundtrack their sci-fi productions.

The most famous example, of course, is the Doctor Who theme tune, written by Ron Grainer and transformed by the late Delia Derbyshire into an electronic music masterpiece for the BBC's in-house library music unit, the Radiophonic Workshop. In recent years, reissues of the original programme's incidental music have sold successfully. Subsequent releases of library music by Derbyshire, Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe have recovered other treasure troves.

But this summer has seen the first major retrospective of individual Radiophonic Workshop artist. The artist honoured is the late John Baker, and the two volumes of The John Baker Tapes have been released by Trunk Records, the pioneering library, soundtrack and jazz label committed to recovering and reissuing lost recordings.

The tapes include idents for news programmes, music from the Dial M for Murder TV series and Ridley Scott's first short film, and the composer himself describing how he made a nine-second electronic track for the Woman's Hour letters slot. Baker's description sums up the sheer amount of work involved in the electronic age before modem synthesisers: not only did he have to record the sound of water pouring from a cider bottle, isolate a note and play it backwards, but he also had to cut every note to make it fit his complicated syncopated melody.

Label boss Jonny Trunk has received lots of emails about one Baker track in particular: an electronic treatment of a Welsh folk song, Tros Y Gareg, which BBC Cymru used as their theme music in the early 1960s. As with the music for Doctor Who, he agrees that people seem to be drawn nostalgically to the music they heard as young children. What's more striking is music that we think of as edgy and experimental now was often used in children's TV and music and movement classes in schools at the time.

But what are the other reasons for library music having such a revival? Trunk has several theories. In the late 90s, he says, reissues of albums like the Dawn of the Dead soundtrack, a record full of strange library music cues, pricked up the ears of fans and small labels. Then came high-profile acts such as the Chemical Brothers, who sampled the Studio G library track Asian Workshop by James Asher on their 1999 album, Surrender, and Jay-Z's Stick 2 the Script in 2000, which sampled Nick Ingman's KPM track Under Pressure.

"Library music became this huge untapped area of sound that brought together all sorts of genres from classical to jazz, from rock to electronics," he adds. And although hip-hop and dance acts had always searched for strange records to sample, now the interest went wider. "People got excited about library music because every other musical area had been pillaged for years. Suddenly all this relatively unknown, relatively underrated, non-commercial music appeared, and they couldn't wait to explore it."

Small labels that are still active such as Studio G — creators of the BBC snooker theme music and a future recipient of the Trunk retrospective treatment — started to get phonecalls about their quirkier records. Label boss John Gale was overwhelmed by the attention, but also delighted. "It was quite extraordinary, but I'm glad people liked it. After all, this music was made in the days of the pirate radio boats, so a lot of it was crazy and naughty." This was music that also had to made behind closed doors, he adds, as the Musicians Union didn't allow its members to make library records. Therefore, the people who made them were even more willing to experiment.

The rarity of many library albums also makes them (covetable to the serious record collector, and the growth of eBay and similar websites in the last decade helped these people find the treasures they craved.

However, many record collectors weren't happy when the reissue boom began in earnest. That's what Tim Lee, the British-born MID of Brooklyn-based label Tummy Touch. Records, discovered when he reissued the rare and much-loved early 1970s KPM 1000 series in 2007, featuring top British musicians like John Cameron and Alan Parker. Lee thought collectors would be delighted that these albums were now available. Instead, many were irritated that their treasured vinyl LPs, worth upwards of £500 each could now be bought on CD for £9.99. This annoys Lee, especially because of the essential nature of library music. "Library music was never supposed to be expensive," he says. "By its nature, it was utilitarian and designed to be used as cheaply as possible."

There's a snobbery here, Lee says, and he knows of some collectors who have spent years searching for records that could easily be obtained by contacting the labels directly. "People forget that these records were made to be used and heard often, rather than being treated like fetishistic objects," he says. "So by distributing these sounds to more and more people, labels like ours treat the music in a similar way to its initial intentions. I don't see what's wrong with that."

Neither do the other label bosses and musicians who are clamouring to reissue it or use it. If you open your ears in 2008, you will hear the stuff everywhere In rock and hip-hop, for instance; Beck's latest album, Modern Guilt, uses library samples, while Dangermouse, its successful producer, works with library-loving bands such as the Shortwave Set. Elsewhere, the huge interest in Delia Derbyshire's lost tapes should encourage the BBC to unlock their plentiful archives.

But more than anything, the most exciting thing about library music is that this source of untapped sound still has a long way to flow, says Lee. "And perhaps hearing music that raw and spontaneous will only encourage people to make music that's similarly adventurous. Music that will be precious and rare for the right kinds of reasons."

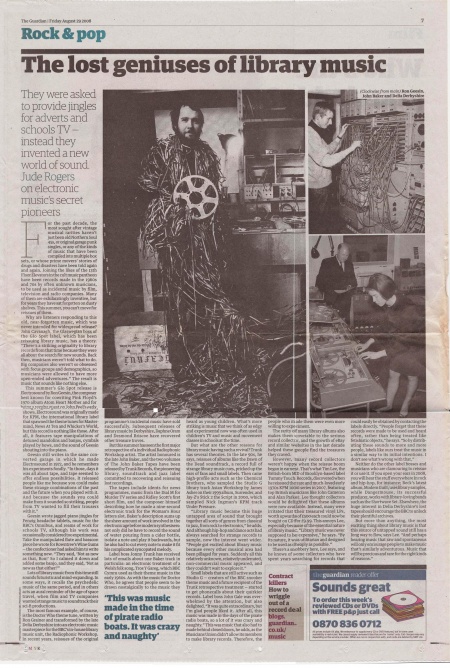

Caption: (Clockwise from main) Ron Geesin, John Baker and Delia Derbyshire

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Rogers, Jude (2008-08-29). The lost geniuses of library music. The Guardian p. 7.

- MLA 7th ed.: Rogers, Jude. "The lost geniuses of library music." The Guardian [add city] 2008-08-29, 7. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Rogers, Jude. "The lost geniuses of library music." The Guardian, edition, sec., 2008-08-29

- Turabian: Rogers, Jude. "The lost geniuses of library music." The Guardian, 2008-08-29, section, 7 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=The lost geniuses of library music | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_lost_geniuses_of_library_music | work=The Guardian | pages=7 | date=2008-08-29 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=24 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=The lost geniuses of library music | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_lost_geniuses_of_library_music | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=24 December 2025}}</ref>