The men with the real sonic screwdrivers

- Publication: The Daily Telegraph

- Date: 2013-07-04

- Author: Matthew Sweet

- Page: 26

- Language: English

How were the amazing sound-effects in 'Doctor Who' originally created? As the Proms celebrates 50 years of the show, Matthew Sweet travels back in time ...

For Proust, it was the taste of a madeleine. For me, it's the sound of a Drashig. It starts as a low snuffle from deep below the ground. Then comes the full-throated howl of a monstrous alien - part fox, part Lambton Worm - surging towards Jon Pertwee with only one thing on its mind. As the roar reaches its climax, another element crashes in: that sliding electronic whine that tells you Doctor Who has reached another cliffhanger. If you render it as a word, you end up with something like eeeeeeeooooowww, but that looks preposterous - and preposterous is not how it sounds.

On July 13, Doctor Who will raise the rafters of the Albert Hall in a Prom programme (repeated on July 14) that celebrates 50 years of the show. In the space between a new composition by Julian Anderson and François-Xavier Roth conducting Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, the BBC National Symphony Orchestra of Wales will materialise - and use the music of Murray Gold to conjure armies of Cybermen, swarms of Daleks, hosts of Weeping Angels.

There have been Doctor Who Proms before, but for the first time the repertoire will reflect the deeper history of the show - for much of which it was not the prestige production it is today, but the object of the BBC's institutional indifference. In those days, money was tight, time even tighter. Many directors were forced to endure the moment when the monster arrived on set looking slightly less fearsome than on it had on paper or - in at least two cases - more like a giant green phallus than anyone had anticipated. But the sounds of Doctor Who were budget-proof, and as avant-garde as anything on the Third Programme.

The habit of experimentation was formed early: from its inception, Doctor Who required sounds the library could not furnish. Verity Lambert, the founding producer, recruited Brian Hodgson of the radiophonic workshop, a cabal of tapebotherers who occupied a couple of rooms at the BBC's Maida Vale studios. She asked for the sound of "the rending of the fabric of time and space" - so he took his mother's front door key, scraped it across the strings of a broken piano, and used feedback effects and his razor blade to raise the thunder of the Tardis engines.

For the theme tune, Lambert wanted to commission a work from Les Structures Sonores, a Parisian collective that coaxed music out of sculptures. When she heard what fee they expected, she returned to Maida Vale and the Cambridge-educated mathematician Delia Derbyshire, one of the sharpest minds in the workshop. Derbyshire took a simple tune composed by Ron Grainer and, using a bank of valve oscillators, concocted the timelessly strange swoops and pulses of the Doctor Who theme - a process that required her to unspool the tape far out into the corridor. "Did I write that?" asked Grainer, when he listened to Derbyshire's finished work. "Almost," replied Lambert.

With this precedent set, Doctor Who's sculptors of sound were free to be as radical as they liked. Tristram Cary - founder of the first electronic studio at the Royal College of Music - summoned a clanking, growling atmosphere for the first appearance of the Daleks. Richard Rodney Bennett, a promising pupil of Pierre Boulez, created wild woodwind flourishes for the Doctor's visit to 15th-century Mexico. The fiercely intellectual Carey Blyton composed lurching modern jazz themes on ancient instruments: humanoid reptiles emerged from the earth to a krumhorn accompaniment; the ophicleide heralded the appearance of the Cybermen. Dudley Simpson, a former conductor for the Borovansky ballet, employed water-gongs, car springs, a church organ and the first Moog synthesizer to create enormous soundscapes with a tiny band of session players: he became the programme's longest-serving composer.

Maida Vale, though, continued to be the source of Doctor Who's most intense sonic experiments. Malcolm Clarke, a wild-eyed, foul-mouthed maverick from the workshop, used a vast machine called the EMS Synthi 100 to add ear-bleeding dissonance to a story about attacks on British shipping by a race of beaky underwater lizards. Using skills he'd developed building clandestine radio sets in German POW camps, the engineer Dave Young constructed a sound-sampling device called the Crystal Palace - a Perspex box that housed rotating vanes, a Dictaphone motor and the gold nib of a Conway-Stewart fountain pen. His colleague Brian Hodgson deployed it to build a pulsing wall of sound for the Krotons - Doctor Who's take on the student riots of 1968. The soundtrack has just come out on CD. Listening to it is like being brainwashed by the CIA at a Stockhausen gig.

Dick Mills was a member of the radiophonic workshop from the start. Between 1972 and 1989, when writers typed lines like "K9 blasts the robot parrot out of the air" or "the Doctor turns into a cactus" or "Sputnik collides with a 1950s bus" - it was his job to construct a sound to persuade viewers that such things might be possible. "There was a principle I followed," he explains. "If it was a device, robot, something programmable or mechanical, then I would use synthesized noise. If it was a monster that was alive, I'd only use organic sounds." A budgie's chirrup became the opening gambit of an alien ambassador. An outing to the pig farm supplied the squeals of the Marshmen of Alzarius. "One of the best things for angry dragons was puppies fighting. And obviously some organic sounds would be me trying to make bodily functions over a microphone."

Sometimes Dick's appetite for experiment was greater than that of his directors. One of his last jobs on Doctor Who was to modulate the firepower of the Happiness Patrol, a gang of sadistic middle-aged cheerleaders from the planet Terra Alpha. "I wanted to get away from the usual bang-crash noise of gunfire," Dick recalls. "I wanted everyone who got shot by the Happiness Patrol to die of intense pleasure. I was trying to think up an enveloping orgasmic sound." But as he prepared to make Meg Ryan I'll have-what-she's-having noises into his Vocoder, the director went cold.

"He said, 'I like the idea, but there is a chase sequence and some of these shots are going to ricochet. How are you going to make an orgasmic sound bounce off the walls?'" In May 2009, some of the surviving alumni of the workshop got together at the Roundhouse in Camden. Under the musical directorship of Mark Ayres - a Doctor Who composer who saved the workshop's archive from chaos and destruction - they emerged, in white lab coats, and took up their positions at analogue synths. The air thrummed and threshed with noise. An eager crowd of students danced gamely to incidental music from a programme made before they were born. And something peculiar happened to the fabric of the universe.

I've made my Drashig confession. Doctor Who fans in every walk of life have something similar alive in their subconscious. For Naomi Alderman, one of Granta's Best Young Novelists, it's the radar waggle of K9's ears. For the philosopher Ray Monk, it's the Tardis in flight. The playwright Mark Ravenhill owned the Doctor Who Sound Effects LP as a child: "That background beat they used for Dalek spaceships still makes me a bit trembly." For the novelist Jenny Colgan it's the cascading chords that accompanied Tom Baker's regeneration into Peter Davison. Something stirs in Mark Gatiss - an architect of modern Doctor Who - when he hears the roar of a robotic Yeti. (A sound achieved by reversing a recording of a flushing toilet.)

It began half a century ago in Maida Vale, when Brian Hodgson scraped that key across a broken piano, and Delia Derbyshire fired up her oscillators and set her tape machines in motion. The sounds they crafted were an attempt to imagine a journey through time and space - but the passing of half a century has allowed those sounds to acquire the power they were designed to evoke. Hear the rising roar of the Tardis engines, the howls of that famous theme, and something happens that it would take a Proust to properly describe. Suddenly it's 1963. And 2013. And it's for ever.

The 'Doctor Who' Proms are on July 13-14. The events are sold out but will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3

"I wanted everyone who got shot to die of intense pleasure, an orgasmic sound

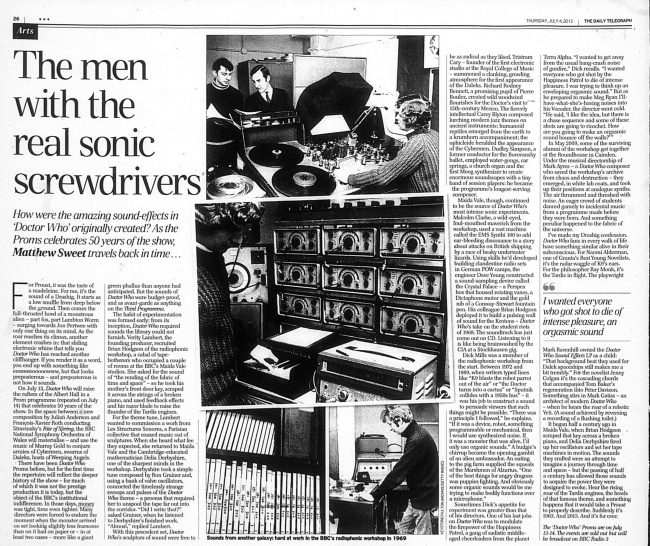

GRAPHIC: Sounds from another galaxy: hard at work in the BBC's radiophonic workshop in 1969

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Sweet, Matthew (2013-07-04). The men with the real sonic screwdrivers. The Daily Telegraph p. 26.

- MLA 7th ed.: Sweet, Matthew. "The men with the real sonic screwdrivers." The Daily Telegraph [add city] 2013-07-04, 26. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Sweet, Matthew. "The men with the real sonic screwdrivers." The Daily Telegraph, edition, sec., 2013-07-04

- Turabian: Sweet, Matthew. "The men with the real sonic screwdrivers." The Daily Telegraph, 2013-07-04, section, 26 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=The men with the real sonic screwdrivers | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_men_with_the_real_sonic_screwdrivers | work=The Daily Telegraph | pages=26 | date=2013-07-04 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=2 June 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=The men with the real sonic screwdrivers | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/The_men_with_the_real_sonic_screwdrivers | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=2 June 2025}}</ref>