Difference between revisions of "Making up is hard to do"

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) (Created page with "{{article | publication = The Newcastle Journal | file = 1983-12-16 Newcastle Journal.jpg | px = 550 | height = | width = | date = 1983-12-16 | author = | pages = | langua...") |

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| width = | | width = | ||

| date = 1983-12-16 | | date = 1983-12-16 | ||

| − | | author = | + | | author = Sue Hercombe |

| − | | pages = | + | | pages = 6 |

| language = English | | language = English | ||

| type = | | type = | ||

Latest revision as of 16:38, 1 January 2019

- Publication: The Newcastle Journal

- Date: 1983-12-16

- Author: Sue Hercombe

- Page: 6

- Language: English

SCREEN make-up is not just a matter of powder and paint. Expertise in other matters, including blood and the other stuff, is all part of the job, SUE HERCOMBE reports.

THE make-up may be dramatic, but the stories from the make-up artist are equally so.

What a great performance, for example, Anthony Ainley gave as The Master in a recent Dr. Who episode. Called upon to disintegrate in a flood of green slime, he actually looked as though he was drowning.

"Not surprising," reveals Dorka Nieradzik, BBC make-up designer who worked on that particular series, "he was" The make-up team had positioned the slime to flow as Mr. Ainley fell forward, but when it came to filming. he actually fell backward, and the evil stuff nearly choked him. Fortunately The Master survived, doubtless to fight another battle with the redoubtable doctor.

Dorka Nieradzik was in Newcastle this week as part of the Tyneside Cinema's Dr. Who festival—returning to the city where she trained as a hairdresser some 15 years ago, later going on to study at the local art college and thence to the BBC.

Illusion

She arrived with the aim of dispelling an illusion that make-up artist's "are just powder-puff girls, in it for the glamour." And certainly she established that make-up design is a sophisticated business requiring fine attention to detail and meticulous historical research.

The interest was largely with Dr Who although a substantial part of Dorka's audience seemed to comprise students from her old college, many of them quite clearly hopeful of careers in television makeup. There was much debate about spirits and adhesives, plaster-of-Paris and plastic, and a good deal of surprise when the expert revealed that, on most occasions, Bostik was quite satisfactory for the creation of jowls or the addition of beards.

It was surprising, too, to learn just how much a make-up designer needs to know about the unlikeliest subjects. Discussing bubonic plague—a subject close to Dorka's heart after spell working for By The Sword Divided—she demonstrated acute knowledge of boils, pains and the visual symptoms of dehydration. "I spent a lot of time talking about the plague with the BBC doctor.

It is necessary—indeed essential—to know because there is always some wise guy on the other side of the small screen yearning point out a makeup error.

Take blood for a start. "If somebody is stabbed in the lungs, blood come out his mouth," says Dorka

"If he's stabbed in the stomach, then it just comes out of the wound. And bodies look different according to how people die. Somebody who's drowned is a different colour from somebody who's had a heart attack." Or bubonic plague, of course. It is the makeup designer's job to know.

Research for By The Sword Divided led Dorka to discover a great deal about make-up trends in the 17th Century—much of which she was unable to use on the drama's characters. "I made a list, two columns. One showed the reality—that people died before they reached old age. that they had little hygiene, that their teeth were mostly rotten. The other listed the needs of the production—that there was romance, that women were described as pretty, that some me were meant to be handsome now you can't have romantic close-ups showing rotten teeth. So we had to cheat on the truth..."

She was sorry, though, that there was little chance to utilise a piece of research into "patches"-the 17th Century fore runner of beauty spots—which women wore to cover boils and blemishes on their faces.

"I also discovered that the women wore false eyebrows made from mouse skin. Just imagine the white, lead-based makeup, the patches and the eyebrows. Some of them must have looked quite horrific'"

But it wasn't, alas, quite what the director wanted, although a genuine character Dorka unearthed—a tinker who travelled the country displaying numerous patches which he sold to fastidious ladies—was incorporated briefly into the script.

Not so with the process the 17th Century used for bleaching hair—a mixture of dogs urine and rhubarb. "I thought it would be quite lovely it we could have the lady of the house calling for her bleaching lotion, and the maid running round with a bowl after the household dog." This time the director disagreed.

If research is part of the job on historical dramas, then creativity and imagination are the essentials for Dr. Who.

How to transform Stratford Johns into a frog and still demonstrate to the viewer that this is the beloved Barlow? Dorka did it. Weird and wonderful creatures from throughout the galaxies have received their finishing touches in her department.

Make-up, she explains, works closely with the visual effects, costume, set design and production departments.

Each takes away a copy of the script and then meets to discuss the ideas that leap from the page.

Green faces, fins, seed-pods growing from heads, nothing is impossible.

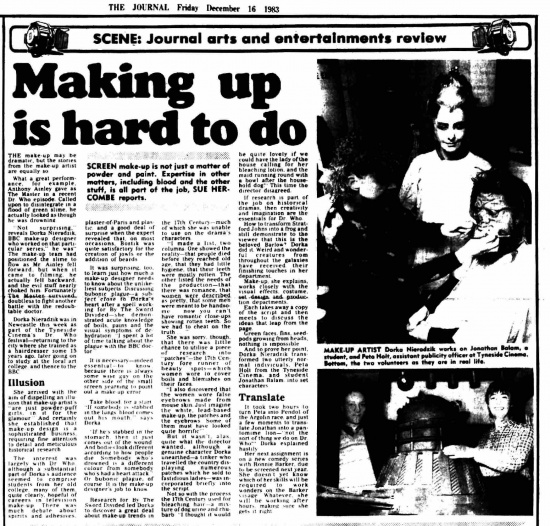

And to prove her point, Dorka Nieradzik transformed two utterly normal individuals, Peta Holt from the Tyneside Cinema, and student Jonathan Balam into set characters

Translate

It took two hours to turn Peta into Pendol of the Argolin race, and just a few moments to translate Jonathan into a pantomime lion—"not the sort of thing we do on Dr. Who" Dorka explained hastily.

Her next assignment is on a new comedy series with Ronnie Barker, due to be screened next year. She doesn't yet know which of her skills will be required to work wonders on the Barker visage. Whatever, she will be working after hours, making sure she gets it right.

Caption: MAKE-UP ARTIST Dorka Nieradzik works on Jonathan Balam, a student, and Peta Holt, assistant publicity officer at Tyneside Cinema. Bottom, the two volunteers as they are in real life.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Hercombe, Sue (1983-12-16). Making up is hard to do. The Newcastle Journal p. 6.

- MLA 7th ed.: Hercombe, Sue. "Making up is hard to do." The Newcastle Journal [add city] 1983-12-16, 6. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Hercombe, Sue. "Making up is hard to do." The Newcastle Journal, edition, sec., 1983-12-16

- Turabian: Hercombe, Sue. "Making up is hard to do." The Newcastle Journal, 1983-12-16, section, 6 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Making up is hard to do | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Making_up_is_hard_to_do | work=The Newcastle Journal | pages=6 | date=1983-12-16 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=13 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Making up is hard to do | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Making_up_is_hard_to_do | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=13 December 2025}}</ref>