Difference between revisions of "Rovers' returns"

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) (Created page with "{{article | publication = The Times Literary Supplement | file = 2005-04-29 TLS.jpg | px = 550 | height = | width = | date = 2005-04-29 | author = Roz Kaveney | pages = 20 |...") |

John Lavalie (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

The fans are especially relevant when considering Doctor Who's return to BBCI, because both the production team and the large starting audience reflect the continued loyalty of viewers who never entirely accepted the show's cancellation as a rational market decision. For those who care, there was a falling-off after the years in which Tom Baker played the Doctor's fourth version (1974-81), but Sylvester McCoy, the Doctor at the time of cancellation, in 1989, was far from the worst of his successors. In fan mythology, cancellation was an arbitrary decision by Michael Grade and so something that the BBC might reverse at any time. | The fans are especially relevant when considering Doctor Who's return to BBCI, because both the production team and the large starting audience reflect the continued loyalty of viewers who never entirely accepted the show's cancellation as a rational market decision. For those who care, there was a falling-off after the years in which Tom Baker played the Doctor's fourth version (1974-81), but Sylvester McCoy, the Doctor at the time of cancellation, in 1989, was far from the worst of his successors. In fan mythology, cancellation was an arbitrary decision by Michael Grade and so something that the BBC might reverse at any time. | ||

| − | This seemed less likely after a failed co-production, in 1997, with Paul McGann as a somewhat transatlantic version of the Doctor. But the rise to prominence of the scriptwriter Russell T. Davies has changed matters. Early on in his ground-breaking television drama Queer as Folk, Davies declared himself: his anti-hero Vince was an obsessive "Whovian". Now, in an alliance with various other bright, youngish A-list things — including Mark Gattis of The League of Gentlemen — Davies has persuaded the BBC that the show is viable, again. | + | This seemed less likely after a {{TVM|failed co-production}}, in 1997, with Paul McGann as a somewhat transatlantic version of the Doctor. But the rise to prominence of the scriptwriter Russell T. Davies has changed matters. Early on in his ground-breaking television drama Queer as Folk, Davies declared himself: his anti-hero Vince was an obsessive "Whovian". Now, in an alliance with various other bright, youngish A-list things — including Mark Gattis of The League of Gentlemen — Davies has persuaded the BBC that the show is viable, again. |

| − | The first three episodes are at once enjoyable in themselves and a celebration of the show's past — the trip to the far future and the terrifying Victorian ghost story are both plots the show repeated time and again; a repetition known, when viewed favourably, as playing to your strengths rather than as mere obsession. Christopher Eccleston is a hipper, sexier Doctor than we were used to in the past — less a scarily dour grandfather or wonderful mad uncle than a friend's very cool elder brother. But the show's principal strength is Billie Piper as Rose, the new companion. She is clearly a post-Buffy consort, the type who can swing on a rope and knock an animated shop-window mannequin flying. Rose is attractively vulnerable, seeing the wonder of the Earth's end, but also being upset by it, and possessed of a common sense that counterpoints the Doctor's sometimes naive idealism. She is also what is commonly known as a "Mary Sue" — an unironic reflection of the writers' and fans' desire to get in there and help the Doctor out (while managing to stay pretty). At the same time, she is a modern working-class woman, with an affecting back story — a childhood on a London estate as the only daughter of a needy, single mother. | + | The first three episodes are at once enjoyable in themselves and a celebration of the show's past — the trip to the far future and the terrifying Victorian ghost story are both plots the show repeated time and again; a repetition known, when viewed favourably, as playing to your strengths rather than as mere obsession. Christopher Eccleston is a hipper, sexier Doctor than we were used to in the past — less a scarily dour grandfather or wonderful mad uncle than a friend's very cool elder brother. But the show's principal strength is Billie Piper as Rose, the new companion. She is clearly a post-Buffy consort, the type who can swing on a rope and knock an animated shop-window mannequin flying. Rose is attractively vulnerable, seeing the wonder of the Earth's end, but also being upset by it, and possessed of a common sense that counterpoints the Doctor's sometimes naive idealism. She is also what is commonly known as a "Mary Sue" — an unironic reflection of the writers' and fans' desire to get in there and help the Doctor out (while managing to stay pretty). At the same time, she is a modern working-class woman, with an affecting back story — a childhood on a London estate as the only daughter of a needy, single mother.}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

Revision as of 12:21, 27 July 2014

- Publication: The Times Literary Supplement

- Date: 2005-04-29

- Author: Roz Kaveney

- Page: 20

- Language: English

For people who were even mildly devoted to it, the cult science-fiction series Doctor Who was never just a television programme. During the 1960s, which Doctor you regarded as the best was one of those things that said something about you — like which Beatle you thought of as your special imaginary friend. Other fans would ask the question and then look at you with cold eyes if you gave the wrong answer. Like other mythopoeic objects of pop-culture love — Sherlock Holmes and Buffy the Vampire Slayer both spring to mind — the Doctor was a secular messiah, who saved people but also helped them to save themselves. Like Sherlock and Buffy, only rather more often, he died and was reborn; far more than either of them, he was as alien enigma onto whom both fans, and new actors playing the part, could project whatever they chose.

Then there were his companions. Almost all such figures have sidekicks, to be rescued or occasionally to assist in rescuing, to sit still during expository speeches, to act as voices of conscience or realism. Doctor Who had many such; they were eye-candy for the parents of the children and adolescents at whom the show was aimed, but sometimes more than that Leela, the pragmatic barbarian, for example, or Romana, the ultra-sophisticate.

The fans are especially relevant when considering Doctor Who's return to BBCI, because both the production team and the large starting audience reflect the continued loyalty of viewers who never entirely accepted the show's cancellation as a rational market decision. For those who care, there was a falling-off after the years in which Tom Baker played the Doctor's fourth version (1974-81), but Sylvester McCoy, the Doctor at the time of cancellation, in 1989, was far from the worst of his successors. In fan mythology, cancellation was an arbitrary decision by Michael Grade and so something that the BBC might reverse at any time.

This seemed less likely after a failed co-production, in 1997, with Paul McGann as a somewhat transatlantic version of the Doctor. But the rise to prominence of the scriptwriter Russell T. Davies has changed matters. Early on in his ground-breaking television drama Queer as Folk, Davies declared himself: his anti-hero Vince was an obsessive "Whovian". Now, in an alliance with various other bright, youngish A-list things — including Mark Gattis of The League of Gentlemen — Davies has persuaded the BBC that the show is viable, again.

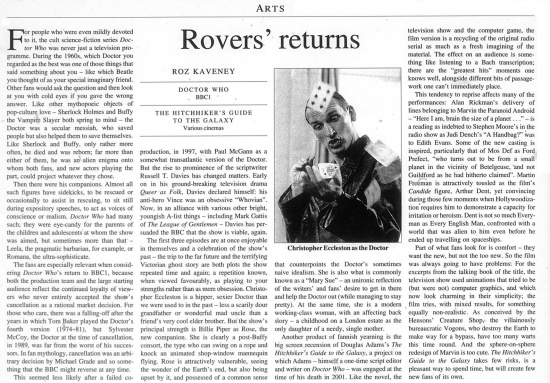

The first three episodes are at once enjoyable in themselves and a celebration of the show's past — the trip to the far future and the terrifying Victorian ghost story are both plots the show repeated time and again; a repetition known, when viewed favourably, as playing to your strengths rather than as mere obsession. Christopher Eccleston is a hipper, sexier Doctor than we were used to in the past — less a scarily dour grandfather or wonderful mad uncle than a friend's very cool elder brother. But the show's principal strength is Billie Piper as Rose, the new companion. She is clearly a post-Buffy consort, the type who can swing on a rope and knock an animated shop-window mannequin flying. Rose is attractively vulnerable, seeing the wonder of the Earth's end, but also being upset by it, and possessed of a common sense that counterpoints the Doctor's sometimes naive idealism. She is also what is commonly known as a "Mary Sue" — an unironic reflection of the writers' and fans' desire to get in there and help the Doctor out (while managing to stay pretty). At the same time, she is a modern working-class woman, with an affecting back story — a childhood on a London estate as the only daughter of a needy, single mother.

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Kaveney, Roz (2005-04-29). Rovers' returns. The Times Literary Supplement p. 20.

- MLA 7th ed.: Kaveney, Roz. "Rovers' returns." The Times Literary Supplement [add city] 2005-04-29, 20. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Kaveney, Roz. "Rovers' returns." The Times Literary Supplement, edition, sec., 2005-04-29

- Turabian: Kaveney, Roz. "Rovers' returns." The Times Literary Supplement, 2005-04-29, section, 20 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Rovers' returns | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Rovers%27_returns | work=The Times Literary Supplement | pages=20 | date=2005-04-29 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 May 2024 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Rovers' returns | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Rovers%27_returns | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=5 May 2024}}</ref>