Sounds from the Dalek age

- Publication: London Evening Standard

- Date: 2005-10-09

- Author: John Aizlewood

- Page: 49

- Language: English

AT the end, all that remained of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was a sign on a door at its former offices in Maida Vale. The BBC closed the workshop in 1997, after it completed the soundtrack to Michael Palm's Full Circle. The sign was quietly removed this year. However, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop will not die. Artists such as Orbital and Aphex Twin, who grew up absorbing its music from Blue Peter and a host of children's programmes, cite the workshop as a primary influence. Moreover, the facelessness of the institution has only served to increase its mystique.

"Initially, the composers weren't even credited. This did cause resentment," says Mark Ayres, a workshop composer who now curates its legacy and hoard of 3,500 reels of soundtrack tape from such programmes as Tomorrow's World, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Body in Question, Blake's Seven, Quatermass and the Pit, and myriad plays and documentaries.

This week two albums, BBC Radiophonic Music, from 1968, and The Radiophonic Workshop, from 1975, have been rereleased. They don't include the workshop's best-known work on Dr Who, which is being released as a 20-volume set, but they do showcase its groundbreaking use of railway sleepers, popping champagne corks and, in Time To Go, a version of the nursery rhyme Oranges and Lemons constructed from the Greenwich time signal.

The workshop made its debut in 1958, when, with little else to do, much of the country listened to Samuel Beckett's All That Fall on the Third Programme. Before then, the BBC had augmented speech with basic sound effects and there were occasional innovations such as The Goon Show's alteration of tape speeds. As higher production values developed in radio and television, the corporation began to think about the idea of a department which producers could commission to create sound effects and music. At first a group of super-dedicated engineers and composers simply worked late, playing with sound and electronics to help programmes.

Eventually, even the BBC, a bureaucracy with the turning circle of the Ark Royal, realised that a special department was needed and formalised the arrangement. The creative maelstrom that was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (its very name suggesting a white-coated celebration of utilitarian values) began, confirming how times were changing.

Its best-known composer, Delia Derbyshire, died last year, aged 64. She was a trained mathematician who enjoyed life to the full. As well as collaborating with Yoko Ono, Brian Jones, Pink Floyd and the composer Peter Zinovieff, she created Time to Go.

Her other stand-out track, Blue Veils and Golden Sands, was created for a World About Us documentary about the Tuareg nomads. It featured her manipulated voice and the ringing of an aluminium lampshade.

"That track encapsulates much of what we were trying to do," Mark Ayres says. "Delia was extraordinary. She always had a book of logarithm tables in her back pocket and would work everything out mathematically" Unheralded and unknown at the time, the workshop's personnel understood that they might be creating for posterity.

"They knew they were doing something interesting and important," Ayres says. "It wasn't nine to five. As with any creative endeavour, the job had to be done when it was needed. If the idea came at five to five, it would have to be worked on through the night." Like the BBC's visual effects and costume departments, the Radiophonic Workshop suffered a slow demise under former director-general John Birt.

THE requirements changed," says Ayres. "The BBC became obsessed with chasing ratings and being cost-effective. Taking chances and being good became less important. The days of taking six weeks to write a television theme were over. What had been a sound factory became a music factory" There were also practical reasons. When the first Fairlight sampler became available in the 19'70s, its cost prohibited mass ownership. Indeed, between them, the Radiophonic Workshop, Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel owned pretty much Britain's entire stock. The advent of the sequencers, soundcards and digital sampling which democratised this type of music-making, coupled with the BBC's yen for tendering, spelled the end for the workshop.

"When programme-makers could choose between spending £300 a minute on the Radiophonic Workshop's music and getting the producer's nephew to do it in his bedroom, that choice became obvious to them," concludes Ayres wistfully. "Whether quality and artistic values were maintained is another matter."

BBC Radiophonic Music and The Radiophonic Workshop are released on BBC Worldwide.

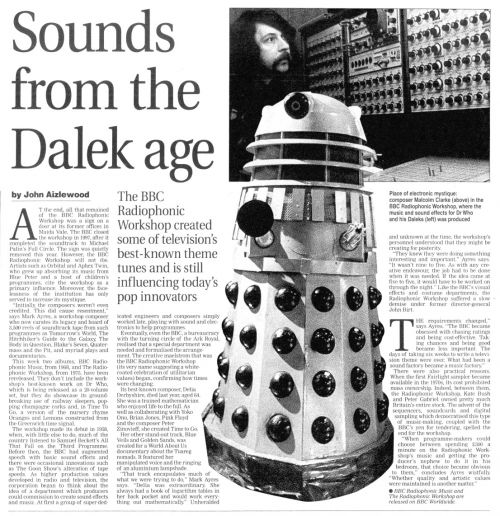

Caption: Place of electronic mystique: composer Malcolm Clarke (above) in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. where the music and sound effects for Dr Who and his Daleks (left) was produced

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: Aizlewood, John (2005-10-09). Sounds from the Dalek age. London Evening Standard p. 49.

- MLA 7th ed.: Aizlewood, John. "Sounds from the Dalek age." London Evening Standard [add city] 2005-10-09, 49. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: Aizlewood, John. "Sounds from the Dalek age." London Evening Standard, edition, sec., 2005-10-09

- Turabian: Aizlewood, John. "Sounds from the Dalek age." London Evening Standard, 2005-10-09, section, 49 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Sounds from the Dalek age | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Sounds_from_the_Dalek_age | work=London Evening Standard | pages=49 | date=2005-10-09 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=24 December 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Sounds from the Dalek age | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Sounds_from_the_Dalek_age | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=24 December 2025}}</ref>