Max Arthur

- Publication: The Times

- Date: 2019-05-23

- Author:

- Page: 52

- Language: English

Unorthodox historian who found his calling after a decidedly rackety career that included acting, decorating and cage dancing

Harry Patch had taken his seat at the Bath literature festival to hear a talk — by Max Arthur, a historian who had documented the First World War in the words of those who had been there, but Arthur asked the 106-year-old veteran of the trenches to read his own words. The room fell silent as "the last fighting Tommy" spoke of the battle of Pilckem Ridge in 1917: "I came across a Cornishman, ripped from shoulder to waist with shrapnel, his stomach on the ground beside him in a pool of blood. As I got to him he said, Shoot me', he was beyond all human aid."

Patch was reading from Forgotten Voices of the Great War (2002), for which Arthur had drawn together testimony from the sound archive at the Imperial War Museum and interviews with men who had survived the trenches and lived until the closing months of the 20th century. "The spoken word's always stronger than the written word," Arthur said. The book sold more than half a million copies.

Although some of his subjects claimed to remember little, he encouraged them to open up. His technique was to place the war years into the context of the soldiers' lives. This could raise difficult questions, he said. "Where was the real life? Was it the journey? Those critical years, when people saw and did horrible things, and then came back to their lives and carried on as they had before?"

A voice from Arthur's Forgotten Voices of the Second World War (2004) maybe answered the question: "One day I saw one of our corporals digging up the road in Chancery Lane when I was walking over to the Law Society. We talked and I was glad to see him. I think he was glad to see me. But there was really nothing to say. It was all gone."

Max Arthur was born in Bognor Regis in 1939, the son of a middle-class woman who had run away from an oppressive background and, as her son would say wryly, "had a good war". He never knew his father, but he did have "quite a few uncles", who would slip him a shilling to keep quiet about their visits, and two brothers with different fathers.

Leaving his local secondary modern school at the first opportunity, Arthur found work on a building site. He was then in the last quota of men called up for National Service when he joined the RAF. It was the making of him, with its rules, discipline and loyalty. The service spotted his potential and helped him through five O levels. He recalled coming back from sentry duty one night to a hangar full of 600 "snoring and farting" men. The man closest to him was so loud that Arthur threw a boot at his head and the man stopped; his last thought as he fell asleep was that he might have killed the snorer.

On demobilisation he went to teacher-training college then taught for a year at a primary school in London. He loved it, as did his pupils, but the headmaster said he was too exuberant. Then came a year at medical school, where he as notable for his bedside manner but little else.

In 1967 he fell for a Jewish girl Who went to work on a kibbutz in Israel. He followed her there and arrived on the day that the Six Day War broke out, recalling that lie got caught in the crossfire and helped to defend the kibbutz.

By the 1970s he was a self-employed painter-decorator in London, but had little clue what he was doing. On one occasion he was redecorating a large house in Clapham where the owner wanted a downstairs lavatory painted in a terracotta colour. Having run out of money, Arthur whitewashed the walls, installed an orange lightbulb and after dark showed off his handiwork to the owner, disappearing before daylight revealed the truth.

His next profession was acting, although his limited success probably came more from his singular looks than any talent. On one occasion he was flown to Italy to star in an advertisement directed by Luchi-no Visconti for an Italian car. No one had thought to check whether Arthur could speak Italian or drive; he could do neither.

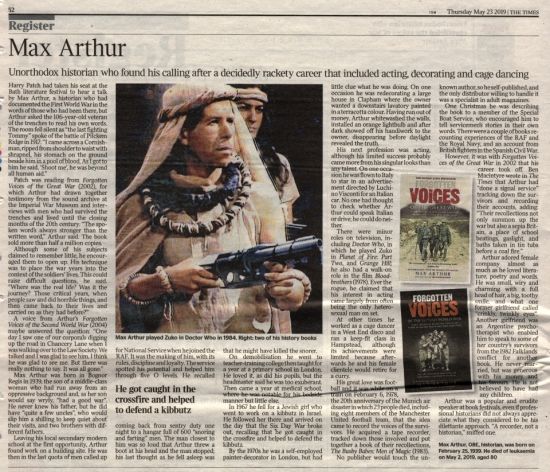

There were minor roles on television, including Doctor Who, in which he played Zuko in Planet of Fire: Part Two, and Grange Hill; he also had a walk-on role in the film Blood-brothers (1978). Ever the rogue, he claimed that his interest in acting came largely from often being the only heterosexual man on set.

At other times he worked as a cage dancer in a West End disco and ran a keep-fit class in Hampstead, although its achievements were limited because afterwards he and his female clientele would retire for a curry.

His great love was football and it was while on a train on February 6, 1978, the 20th anniversary of the Munich air disaster in which 23 people died, including eight members of the Manchester United football team, that the idea came to record the voices of the survivors. He acquired a tape recorder, tracked down those involved and put together a book of their recollections, The Busby Babes: Men of Magic (1983).

No publisher would touch the un known author, so he self-published, and the only distributor willing to handle it was a specialist in adult magazines.

One Christmas he was describing the book to a member of the Special Boat Service, who encouraged him to tell servicemen's stories in their own words. There were a couple of books recounting experiences of the RAF and the Royal Navy, and an account from British fighters in the Spanish Civil War.

However, it was with Forgotten Voices of the Great War in 2002 that his career took off. Ben Macintyre wrote in The Times that Arthur had I "done a signal service" tracking down the survivors and recording their accounts, adding:

"Their recollections not only summon up the war but also a sepia Britain, a place of school beatings, gaslight, and baths taken in tin tubs before a coal fire."

Arthur adored female company almost as much as he loved literature, poetry and words. He was small, wiry and charming with a full head of hair, a big, toothy smile. and what one R former girlfriend called "crinkly, twinkly eyes". Another girlfriend was an Argentine psychotherapist who enabled him to speak to some of her country's survivors from the 1982 Falklands conflict for anopo-book. He never married, but was generous with his believed to have had any children.

Arthur was a popular and erudite speaker at book festivals, even if professional historians did not always appreciate what they considered to be his dilettante approach. "A recorder, not a historian," sniffed one.

Max Arthur, OBE, historian, was born on February 25, 1939. He died of leukaemia on May 2, 2019. aged 80

Caption: Max Arthur played Zuko In Doctor Who in 1984. Right: two of his history books

Disclaimer: These citations are created on-the-fly using primitive parsing techniques. You should double-check all citations. Send feedback to whovian@cuttingsarchive.org

- APA 6th ed.: (2019-05-23). Max Arthur. The Times p. 52.

- MLA 7th ed.: "Max Arthur." The Times [add city] 2019-05-23, 52. Print.

- Chicago 15th ed.: "Max Arthur." The Times, edition, sec., 2019-05-23

- Turabian: "Max Arthur." The Times, 2019-05-23, section, 52 edition.

- Wikipedia (this article): <ref>{{cite news| title=Max Arthur | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Max_Arthur | work=The Times | pages=52 | date=2019-05-23 | via=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=22 May 2025 }}</ref>

- Wikipedia (this page): <ref>{{cite web | title=Max Arthur | url=http://cuttingsarchive.org/index.php/Max_Arthur | work=Doctor Who Cuttings Archive | accessdate=22 May 2025}}</ref>